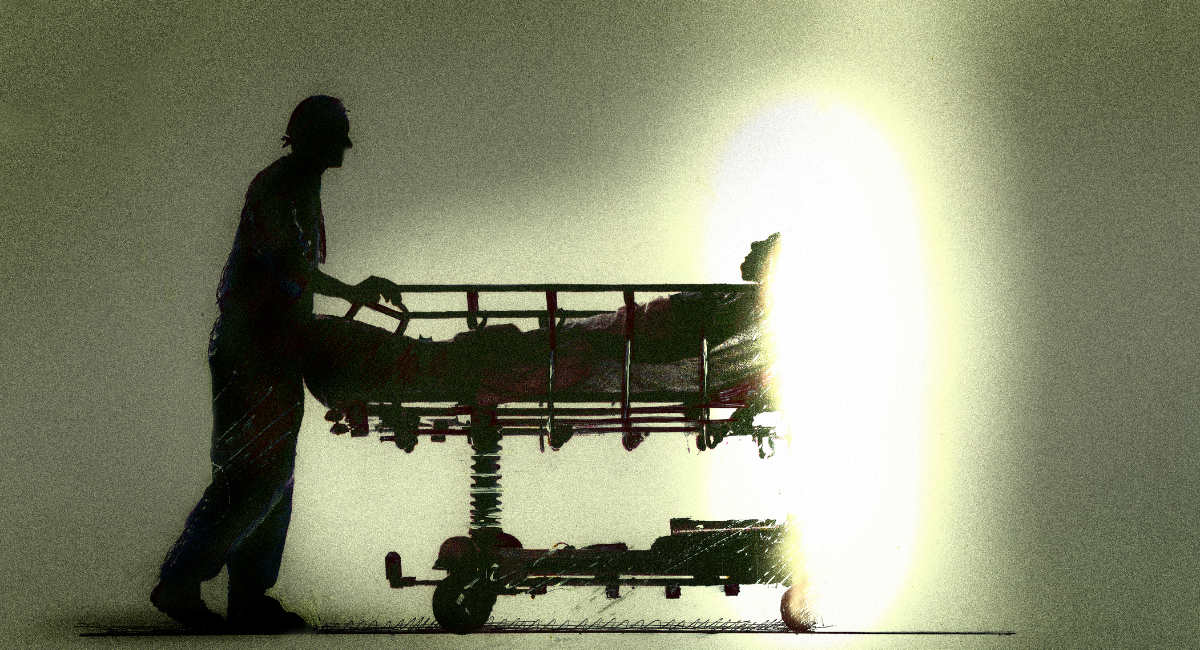

More than 200 people have died by assisted suicide or euthanasia in Queensland, Australia, in just the first six months the practice has been legalized.

Data from the Voluntary Assisted Dying (VAD) Annual Report shows 245 deaths in the period from January 1 to June 30. Those deaths represent an assisted dying rate higher than that of Western Australia after one year, and twice Victoria’s rate after four years. Queensland has broader qualification laws than many of Australia’s other states, requiring that a person be expected to die within 12 months rather than six.

Helen Irving, chair of the Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board, said the laws “are working as intended and they are safe, accessible, and compassionate.”

“We’ve heard really nothing but praise and gratitude, and a sense of relief that it is available,” Sheila Sim, the president of Dying with Dignity Queensland told The Guardian. “And praise and gratitude for the way that their requests have been dealt with. Compassionately, promptly, people take took the time to explain what was going on, and what would be needed.”

READ: Ethical issues abound as Australian woman’s organs are donated after assisted suicide

Despite the praise, advocates are already pushing to expand the rules surrounding the administration of the laws, with the call to repeal a federal ban that prohibits telemedicine VAD appointments. In its report, the VAD Review Board recommended, “Amendments to the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) to enable carriage services (such as telehealth) to be used for the provision of voluntary assisted dying services.”

That suggestion is facing significant opposition across the country. In April, a group of 1,000 medical professionals united to warn against the allowance of telehealth appointments for VAD, noting that it would be much harder for them to protect against coercion without meeting face-to-face with a patient.

“Further relaxation of criminal codes to facilitate telehealth for VAD assisted suicide would remove protections owed those vulnerable to suicide under duress and in need of palliative care, aged care, and mental health services, especially so in regional and remote Australia,” the group wrote in a letter.

“It is oversimplistic and in breach of a patient’s rights and owed dignity in healthcare to imagine competence, informed consent, lack of coercion, mental illness and comprehensive health care or palliative care needs can be adequately assessed using telehealth by VAD doctors.”