If you hoped pro-abortion legal analysts’ reaction to the Supreme Court’s Texas abortion ruling might at least be a cut above the reactions of garden-variety pro-abortion bloggers, think again.

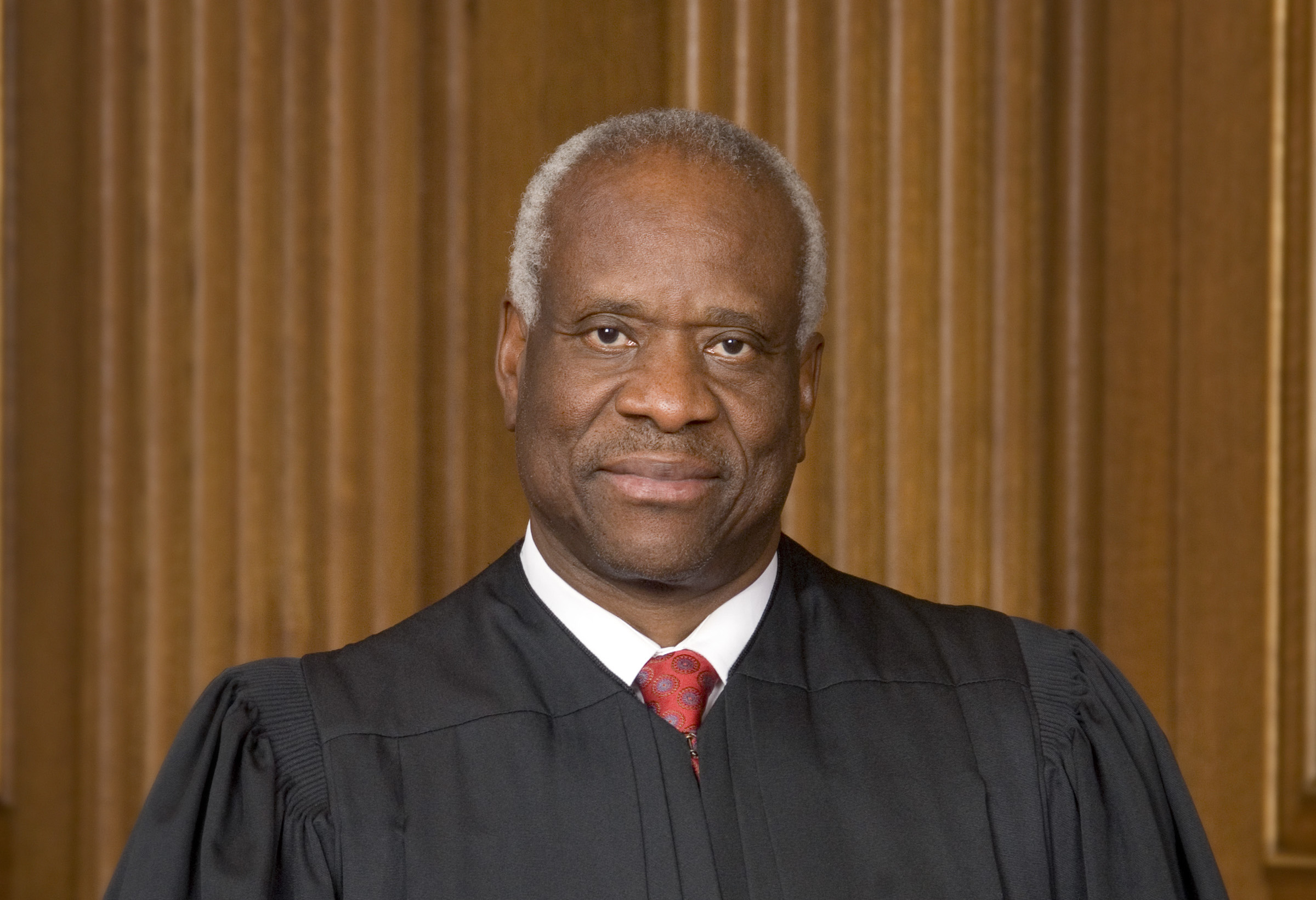

At LawNewz, Elura Nanos presumes to dismantle three “really, really lame” arguments Justice Clarence Thomas put forth in his blistering dissent from the majority’s judicial malfeasance. However, I don’t think anyone will be shocked to learn that the only lame arguments are hers.

Before presuming to lecture one of the greatest living legal minds in the country, Nanos introduces the subject as follows:

Abortion law is an innately complex topic, because the nature of pregnancy is unique in its evolving relationship between an individual woman and another potential human being.

Not really. Abortion precedent may be complex, but that’s only because the Supreme Court started us on a such a convoluted course by deciding it was a constitutional right based on something other than the straightforward text of the Constitution. Properly understood, the Constitution’s answer to abortion couldn’t be simpler: all human beings (which the preborn are—actual, not potential) have the right not to be killed.

The constitutionality of medical regulations is straightforward, too—according to James Madison, the federal government’s powers “are few and defined,” while “those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite.” So Texas should generally be free to make whatever laws are not forbidden by something the Constitution specifically says.

THOMAS: “Today the Court strikes down two state statutory provisions in all of their applications, at the behest of abortion clinics and doctors.”

NANOS: Really? The Supreme Court is operating “at the behest” of abortion clinics and doctors? That’s kind of obnoxious. The millions of liberty-loving Americans who fight for abortion rights do so as advocates for women, not for clinics. The suggestion that our highest Court doesn’t actually care about reproductive rights or Constitutional precedent, but rather, is the puppet of abortion clinics is absurd and offensive.

The only thing absurd and offensive here is that this is exactly what happened. The suit was brought by Whole Woman’s Health, an abortion chain, and the court ruled in their favor, despite WWH’s nearly ten-year record of lawbreaking, substandard health and safety conditions, and egregious negligence — a record that these “advocates for women” decided was good enough for women. So with neither legal merit nor women’s health justifying the decision, what other conclusion is left than Thomas’s?

THOMAS: “To begin, the very existence of this suit is a jurisprudential oddity. Ordinarily, plaintiffs cannot file suits to vindicate the constitutional rights of others. But the Court employs a different approach to rights that it favors.”

NANOS: You have to respect how Justice Thomas is unapologetic in his hypocrisy. The justice is certainly right that lawsuits require that the plaintiff have proper standing to sue. But questions about abortion have always required a “different approach” because pregnancy is inherently different from other subjects. More importantly, the entirety of pro-life rhetoric is founded on the idea of third-party assertion of rights. Every time state governments reach their legislative hands into women’s uteruses, they justify the intrusion with their obligation to protect the unborn; no clearer assertion of the rights of “others” has ever been made.

That’s a lot of certainty for what amounts to “I don’t know what I’m talking about.” Standing to bring a suit in a particular case (which can vary wildly depending on the specifics) and constitutional authority to legislate something (see above) are two entirely different things. I highly doubt Thomas has ever argued that standing is irrelevant for pro-lifers filing lawsuits against pro-abortion laws… just as I doubt there are many law students who make it past their first year confusing such unrelated concepts under the umbrella of “asserting rights.”

Allowing women to get abortions only in some absurdly narrow set of equals outlawing abortion. If Texas had legislated in a manner that would close half its gun stores, the Court would likely have found a similar undue burden on the Second Amendment.

We’ll get to the “undue burden” test in a moment, but here let’s just note the obvious difference Nanos overlooks: the Second Amendment is an actual part of the Constitution expressly guaranteeing the “right of the people to keep and bear arms,” whereas abortion “rights” are projected into the Constitution based on imaginary “penumbras.” Even if the undue burden test was legitimate, the constitutional right being burdened still has to, y’know, exist.

THOMAS: “The majority applies the undue-burden standard in a way that will surely mystify lower courts for years to come.”

NANOS: Maybe I’m some sort of legal genius, but I’m nowhere near “mystified” right now. I’m not even a little bit confused. The Texas law made it super tough for Texan women to get abortions, mainly in that it closed most Texan abortion clinics. Forcing someone seeking a medical procedure to jump through costly and difficult hoops is pretty clearly an “undue burden” – whether we’re using the plain meaning or the legal meaning of those words.

“Some sort of legal genius” who missed two glaring problems with the majority decision. First, the “undue burden” test is a judicial invention rather than a real standard to be found in the Constitution’s text. “Undue burden” doesn’t have a precise legal meaning that can be impartially applied, and it flips the burden of proof from the feds having to prove that their intervention serves a “compelling interest” not otherwise achievable (which is already a departure from Madison’s original explanation of enumerated powers), to the states having to prove they’re playing nice with the judiciary’s favored legal fictions such as Roe v. Wade.

Second, Thomas isn’t making up his own standard. He’s directly calling out this ruling as a repudiation of SCOTUS’s own precedent of upholding various abortion regulations based on the “legitimate interest” Planned Parenthood v. Casey recognized in both “maternal health and in unborn life.”

In fact, his point is that the majority “radically rewrites the undue-burden test” from Casey’s own baseline:

First, today’s decision requires courts to “consider the burdens a law imposes on abortion access together with the benefits those laws confer.” Second, today’s opinion tells the courts that, when the law’s justifications are medically uncertain, they need not defer to the legislature, and must instead assess medical justifications for abortion restrictions by scrutinizing the record themselves. Finally, even if a law imposes no “substantial obstacle” to women’s access to abortions, the law now must have more than a “reasonabl[e] relat[ion] to . . . a legitimate state interest.” These precepts are nowhere to be found in Casey or its successors, and transform the undue-burden test to something much more akin to strict scrutiny.

Nanos says she’s “not quite sure what Justice Thomas finds confusing about that.” Well, reading the justice’s extensive elaboration of his above three points probably would have cleared that up.

Try as they might, abortion apologists cannot change the reality that yesterday’s ruling was rank political manipulation masquerading as law. Abortion-on-demand began in this country with judicial malpractice, and judicial malpractice continues to keep it alive.