Most Americans likely think of the pro-life movement as an outgrowth of Roe v. Wade, but it actually reaches much farther back in time. Roe v. Wade simply accelerated the process by thrusting it into the national limelight.

A book, Defenders of the Unborn by Daniel Williams, takes a comprehensive look at the conception of the pro-life movement. As Williams notes in an Atlantic interview, “Too many historians took for granted that the pro-life movement emerged as a backlash against feminism, and/or as a backlash against the Supreme Court’s decision in 1973.”

Ironically, the early roots of the pro-life movement were considered liberal. Williams notes that “we have been mistaken in some of our assumptions about the political realignments of the late twentieth century, and that the pro-life movement that we have always labeled ‘conservative’ was at one time much more deeply rooted in liberal rights-based values than we might have suspected” (xiv). The pro-life movement, in fact, began as a human rights movement.

It was the pro-life movement’s message of human rights that sustained it through the sexual revolution, the feminist movement, and the social changes of the 1960s. The language of constitutional rights and human dignity allowed for the pro-life movement to build a diverse coalition that grew in strength over the years.

As the political climate shifted in the decades that followed, the message that abortion is a civil rights issue drove the movement. Pro-lifers insisted that abortion was not in the best interest of women and their health, and advocated that women facing crisis pregnancies should receive financial assistance instead.

It was the feminists of the 1960s, however, who hijacked women’s freedoms into an agenda to sell abortion. They began to label abortion as a woman’s fundamental right to control her body and her fertility. The feminist movement catered the message to the public, and abortion became widely acceptable among Americans who adopted the ideals of the sexual revolution.

It soon gained widespread appeal among liberals who valued personal autonomy, individual rights, and human equality, and who accepted some of the values of the sexual revolution of the 1960s, including the idea that the state had no business regulating issues of sex and reproduction between consenting adults. The arguments of the “pro-choice” movement— a term that advocates of abortion rights began using in the early 1970s— seemed to force pro-lifers into conflict with some key liberal ideas. (6)

During this time, the abortion rights movement was also rising, with an infamous abortionist at its helm. Bernard Nathanson, who later converted both to pro-life activism and then to Christianity, writes in his memoir, The Hand of God, of the pro-abortion movement’s foray onto the public stage. He described that by 1969, the movement was preparing for a meeting with national pro-abortion figures, which birthed the group NARAL, and was actively building its coalition. He admits that their agenda was nothing short of eliminating all abortion restrictions:

… We would settle for nothing less than striking down all existing abortion statutes and introducing abortion on demand in their place. Our first target of opportunity was the New York state statute prohibiting abortion unless the pregnancy threatened the life of the pregnant woman. (90)

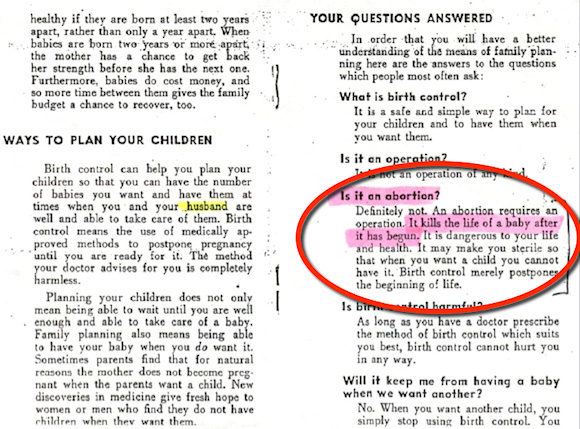

Nathanson’s account also reveals how messaging on abortion has evolved over the decades. In 1952, Planned Parenthood admitted on a pamphlet that abortion “kills the life of a baby” prior to changing its message and branding.

The deceptive media messages the abortion industry crafted were imperative in shaping public opinion, Nathanson reveals. The goal was to cause Americans to believe abortion is not the killing of a child, but reproductive choice. Nathanson admits the abortion lobby sold the message to a press too eager to “rattle the cages of authority.”

The deceptive media messages the abortion industry crafted were imperative in shaping public opinion, Nathanson reveals. The goal was to cause Americans to believe abortion is not the killing of a child, but reproductive choice. Nathanson admits the abortion lobby sold the message to a press too eager to “rattle the cages of authority.”

The manipulation of the media was crucial, but easy with clever public relations, especially a steady drumfire of press releases disclosing the dubious results of surveys and polls that were in effect self-fulfilling prophecies, proclaiming that the American people already did believe what they soon would believe: that all reasonable folk knew that abortion laws had to be liberalized.

In the late sixties and early seventies, the media trenches were peopled young, cynical, politically case-hardened, well-educated radicals who were only too anxious to upset the status quo, roil the waters, and rattle the cages of authority. (90)

In fact, it was only two years after Planned Parenthood’s brochure that the abortion lobby began to intensify its agenda.

In his book Third Time Around, George Grant, offers a comprehensive history of the pro-life movement and marks the change. He notes “In 1954, Planned Parenthood holds an international conference on abortion and calls for reform of restrictive legislation” (128).

Grant expounds further on the developing pro-abortion timeline, writing that in 1966, the National Organization of Women was established with the goal of “liberalization of abortion laws” (129). And one year later, “the American Medical Association reverses its century-old commitment to the lives of the unborn and also begins calling for decriminalization of abortion” (129).

The following year, the United Kingdom legalized abortion, and laws began to follow suit.

“By the end of 1971, nearly half 1 million legal abortions are being performed in the US each year” (129). So by the time Roe v. Wade was decided, abortion was well underway in America.

But Williams notes that while pro-life Catholics fought the wave of feminist opposition and media messaging by insisting “human life…was ultimately more important than individual choice,” (7) the battle continued. By solidifying their argument in the principle that individuals must care for the weaker, pro-lifers won victories in the public square until Roe v. Wade was decided.

In the years after Roe v. Wade, several groups rose to meet the national abortion decision head on. In 1975, many leaders met with Billy Graham for two days to form a biblical response to the new law, forming the Christian Action Council (145). In 1979, the American Life League was formed to parallel and extend the work of National Right to Life. Also in 1979, Francis Schaeffer released Whatever Happened to the Human Race, a book and film series, following by a book in 1981, A Christian Manifesto, which helped “galvanize the nascent pro-life forces (145).” A major impact also came from Dr. Nathanson, who quit the abortion industry and became pro-life.

As the years continued, the abortion battle bounced back and forth, with each side cropping up to a victory before the other side did. Legislation was introduced on Capitol Hill; and in 1987, Planned Parenthood launched “a full-scale negative publications campaign to discredit and close the more than three thousand alternative crisis pregnancy centers around the country” (146). This is a campaign that has not lessened for the abortion chain, which still contends these pro-life centers should not be allowed to operate.

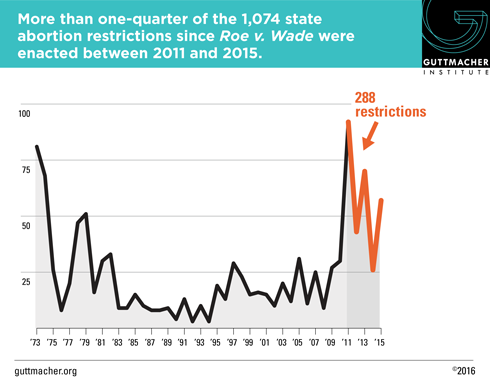

By 2008, when Barack Obama —considered as the most pro-abortion president in American history— was elected, the pro-life movement was ready to meet the challenge. When the 2010 mid-term elections came around, many pro-lifers had been voted into office; and in 2011, they broke records with new pro-life legislation. Throughout both of President Obama’s terms in office, hundreds of pro-life laws have been passed, and the trend continues.

As in the decades that preceded them, pro-lifers today continue their fight to protect the most vulnerable— from the state house to the White House.

Works Cited:

Grant, George. Third Time Around: A History of the Pro-life Movement from the First Century to the Present. Brentwood, TN: Wolgemuth & Hyatt, 1991. Print.

Nathanson, Bernard (2013-02-25). Hand of God: A Journey from Death to Life by The Abortion Doctor Who Changed His Mind (p. 90). Regnery Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Williams, Daniel K. (2015-12-04). Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement before Roe v. Wade (p. 3). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Save