Poll: More UK medical professionals oppose assisted suicide bills than support

Right to Life UK

·

Investigative·By Carole Novielli

Some abortion survivors were kept alive almost a day for experimentation

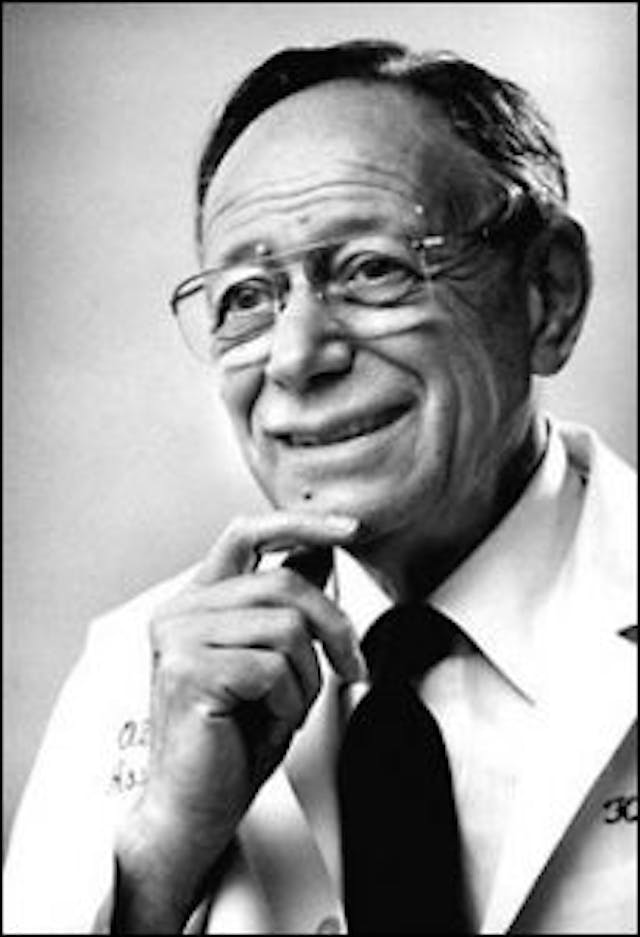

In part one of this series on fetal research, Live Action News detailed a number of experiments conducted on living abortion survivors. Due to the outrage over such experiments reported in the media in the 1970s, the National Research Act established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The commission was chaired by Kenneth John Ryan, MD, an abortionist who also taught others how to do abortions.

A report published by the Harvard Gazette at the time of Ryan’s death states:

President Jimmy Carter appointed Ken to chair the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research.

…When he became the Chief of Staff at the Boston Hospital for Women in 1973, one year after the Roe vs Wade decision, he established the first abortion service in a university hospital and included training in the necessary skills as a routine part of residency education. In 1975 Ken credentialed and granted admitting privileges to Dr. Kenneth Edelin, an African-American, even as he was under indictment for manslaughter in a politically motivated prosecution for performing a legal abortion at Boston City Hospital.

The Ryan Program, which bears the doctor’s name and partners with Planned Parenthood, was established in 1999 to train OB-GYN residents in abortion.

READ: 6 things you might not know about preborn babies in the first trimester

Dr. Paul Ramsey, a Professor of Religion at Princeton University, also served on the commission. He wrote a lengthy opinion in the section entitled, “Moral Issues in Fetal Research,” criticizing NIH definitions of life and death regarding the preborn child, with good reason:

The answer seems clear enough: the difference between the life and death of a human fetus/abortus should be determined substantially in the same way physicians use in making other pronouncements of death… the 1973 NIH proposed guidelines studiously refuses to speak of the previable fetus as “living” or having “life.” By studiously refusing to speak of a previable fetus/abortus who may still be medically “alive” and by leaving the determination of viability entirely to the discretion of physician researchers (not even excluding abortuses with respiration from being deemed previable and entered into experimentation), the American guidelines can be faulted for lack of definitional clarity. Indeed, if and only if the previable fetus is human, unique for certain purposes, and alive in significant medical respects–i.e., if it is not dead–could claims be made that researchers need the knowledge uniquely to be gained by using the fetus/abortus while it is still living, growing and reacting as a tiny, whole fetal human being or entity.

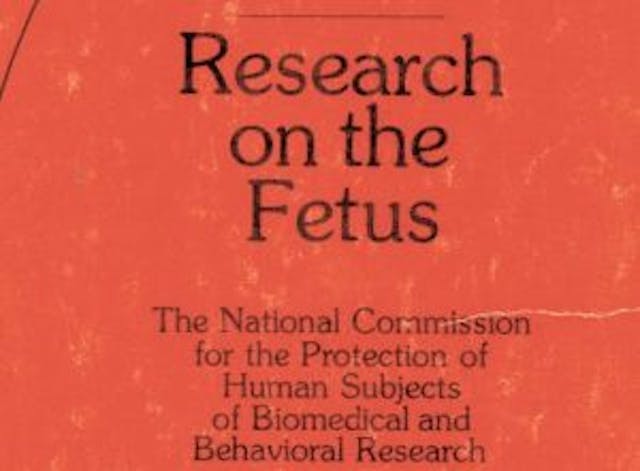

This national commission was tasked to investigate and study research involving abortion survivors, and to recommend whether and under what circumstances such research should be conducted or supported by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). Up to this time, the July 1974 “National Research Act” had ruled that the “Secretary may not conduct or support research in the United States or abroad on a living human fetus, before or after the induced abortion of such fetus, unless such research is done for the purpose of assuring the survival of such fetus.”

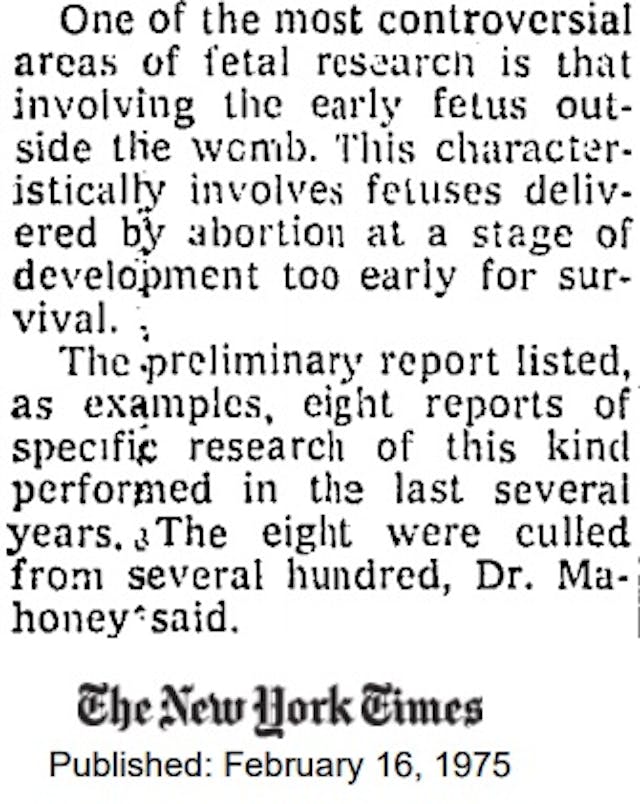

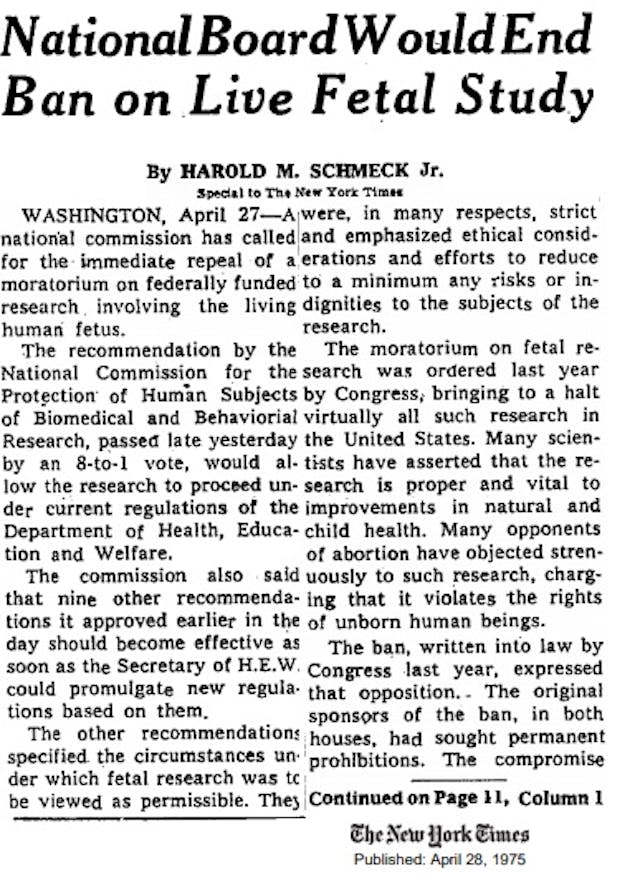

At the time the commission began, a New York Times article detailed how members of the commission had reviewed existing research of human fetuses. Members told the paper that the amount of research already conducted using aborted fetuses was “so substantial as to seem surprising.”

The most controversial form of research the commission found was on the “fetus outside the womb,” involving “fetuses delivered by abortion.” The commission claimed hundreds of reports of such cases had been conducted. Experiments were also conducted on already expired fetuses from spontaneous or induced abortions. Below is a small sample of what the commission found:

Physiologic and Metabolic Studies: Fetal hearts, removed just after death of a fetus following hysterotomy abortion, have been studied to establish physiologic response data.

Studies of the Pregnant Mother: Women undergoing elective midtrimester abortion have been starved for 87 hours before abortion in an attempt to learn the effects of caloric deprivation on pregnancy and to gain some information as to whether the fetus could adapt to fuels other than glucose.

Research With the Previable Fetus Outside the Uterus: To learn whether the human fetal brain could metabolize ketone bodies, brain metabolism was isolated in 8 human fetuses (12-17 weeks’ gestation) after hysterotomy abortion by perfusing the isolated head (the head was separated from the rest of the body). The study demonstrated that, similar to other species, brain metabolism could be supported by ketone bodies during fetal life suggesting avenues of therapy in some fetal disease states.

Another technique for studying the ability of the midtrimester fetus to carry out endocrine reactions used 4 fetuses (16-20 weeks’ gestation) immediately after hysterotomy abortion. The fetuses were perfused through their umbilical veins while being housed in a perfusion tank. Fetal tissues were examined at the end of the study.

After studies with newborn and fetal mice, cutaneous respiration (breathing through the skin) was studied in 15 fetuses (9-24 weeks’ gestation) from induced abortions. The fetuses were immersed in a salt solution with oxygen at high pressure. The fetuses were judged to be alive by a pulsating cord or visible heart beat; if necessary the chest was opened to observe the heart. Four fetuses were supported for 22 hours in this attempt at developing a fetal incubator.

Seven previable fetuses (200-375 grams) from spontaneous or induced abortions were immersed in a perfusion tank and perfused with oxygenated blood through their umbilical vessels. The fetuses survived and moved for 5-12 hours.

Interestingly, in addition to general experimentation, the commission noted that if the fetus could “feel pain” then experimenting on abortion survivors would not be permissible. Of course, that debate continues to linger despite evidence that they do feel pain.

READ: Preborn babies sense not just pain, but light and temperature

Article continues below

Dear Reader,

Have you ever wanted to share the miracle of human development with little ones? Live Action is proud to present the "Baby Olivia" board book, which presents the content of Live Action's "Baby Olivia" fetal development video in a fun, new format. It's perfect for helping little minds understand the complex and beautiful process of human development in the womb.

Receive our brand new Baby Olivia board book when you give a one-time gift of $30 or more (or begin a new monthly gift of $15 or more).

Still, members were mixed:

The fetus in utero or in process of being aborted provides a more difficult ethical analysis than does the dead fetus or the living viable infant. There is a presumption of viability at any stage in gestation for the living fetus as long as it remains inside the uterus. Thus experimentation involving that fetus must have acceptably low risk of any harmful effect on viability or on the potential for meaningful, healthy life. If the process of abortion has begun, the life of the fetus will soon end. There is debate about whether different standards apply in that situation and we disagree in our own analysis.

One view holds that no risks can be imposed that would not be acceptable for the fetus which was continuing life. Another view will accept an increase in risks if the information is important and alternate ways of obtaining the information are not practical, if the methods of the experiment are acceptable in themselves (i.e., would be used in other classes of human subjects), and if the process of dying for the fetus were not altered in an unacceptable way.

In any event, expected benefits from the experimentation still must be clear and must require the use of the human fetus to gain the desired information. Ethical considerations as to sensory perception by the fetus also must be addressed. We know of no evidence to suggest or support a contention that the fetus at midgestation or earlier, when abortions are performed, is aware of pain or has a psychologic fear of death.

The commission ultimately drafted several recommendations, including a restriction on experimenting on living abortion survivors. But their report also recommended that research resulting in “no harm to the fetus” be permitted, so long as that research might benefit other fetuses.

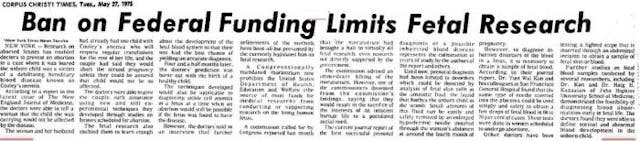

Unfortunately, this did not stop the push for the research nor the push to obtain federal funding. According to a historical timeline of fetal research regulations published in a report by the Institute of Medicine:

After the National Commission issued its report (Report and Recommendations: Research on the Fetus), fetal research following abortion was permitted under subsequent [Department of Health Education and Welfare] DHEW regulations for therapeutic reasons, but otherwise held to the standard of “minimal risk.” Minimal risk means that no more potential harm is tolerated than would be encountered in daily life. In the case of a fetus, almost all interventions exceed minimal risk, and the regulations did not distinguish between fetuses that were carried to term and those intended for abortion. The DHEW regulations, however, contained the possibility of waiver of the minimal risk standard on a project-by-project basis by a complicated procedure to be decided ultimately by an Ethics Advisory Board.

The first Ethics Advisory Board (EAB) was convened in 1978. The sole waiver issued by this body was to test the efficacy of using fetal blood samples for prenatal diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. The charter for the EAB expired in 1980, and despite publication of a draft charter in 1988, it has not been reactivated.

According to CQ Researcher, in 1988, an NIH commission “voted 18–3 to pronounce fetal tissue transplant research ‘acceptable public policy’—a position then unanimously endorsed by the standing advisory committee to the director of the NIH. That advice, however, was rejected in November 1989 by Louis W. Sullivan, the Bush administration’s secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), NIH’s parent department. Sullivan decided instead to extend, indefinitely, the moratorium on NIH funding of fetal tissue research first ordered by the Reagan administration in March 1988. The moratorium barred NIH funding of clinical transplantation studies using tissue from induced abortions.”

However, “The NIH moratorium did not affect privately funded research in the United States.”

Co-chairman on that 1988 NIH panel was none other than Kenneth Ryan, the same abortionist/trainer who chaired the 1970’s commission. When the push for federally funded research failed, Ryan began calling for private funding to experiment on aborted children.

In part three of this series, Live Action News will detail who eventually lifted the ban on federal funding of fetal tissue research and how much taxpayers spend on this research every year.

Editor’s Note, 10/16/18: Links to parts one and three of this series were added.

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Right to Life UK

·

Investigative

Nancy Flanders

·

Investigative

Nancy Flanders

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Angeline Tan

·

Human Rights

Carole Novielli

·

Abortion Pill

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Abortion Pill

Carole Novielli

·