Karla and Gavin Duerson were parents to five children when they got pregnant with another baby. During the pregnancy, doctors began to realize the child would likely have Trisomy 18, often believed to be a life-limiting disorder, and warned the Duersons that their daughter might not survive. But the Duersons insisted their baby be given every chance to survive. Doctors’ refusal to give up allowed their daughter to live longer than anyone expected — and it’s helping to pioneer treatment for other babies with Trisomy 18.

In a press release for the University of Kentucky, Karla Duerson explained how their journey with baby Wylie began. “We did an anatomy scan at 20 weeks, and they detected some problems with her heart and benign cysts that don’t cause problems themselves, but can indicate that there may be a genetic problem,” she said. A non-invasive prenatal screening revealed Wylie would likely have Trisomy 18, and other soft markers made the likelihood even higher, but doctors said they wouldn’t know for sure until after Wylie was born.

The Duersons were referred to UK HealthCare’s Kentucky Children’s Hospital, part of Kentucky Children’s Hospital’s Joint Heart Program with Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, where they met Dr. Louis Bezold, chief of pediatric cardiology. Bezold said Wylie would likely be born with holes in her heart, but they would wait until she was strong enough to perform surgery to repair them.

This, in and of itself, is unusual. Often, children with Trisomy 18 are given nothing more than palliative care, because doctors often present the condition as fatal and not worth treating. If the condition is detected in the womb, parents are frequently pressured to have an abortion.

READ: Mom of daughter with Trisomy 18 fights to change the message for families like hers

“There are parents that are having to advocate for themselves and send their children’s medical records all over the country looking for a surgeon who is willing to do a surgery on a baby who has Trisomy 18,” Duerson said. “And we’re literally less than 10 minutes away.”

A multi-disciplinary team began working with the Duersons in preparation for Wylie’s birth, including the Pediatric Advanced Care Team (PACT), which works on helping children with serious illnesses see an improved quality of life. “While there is no cure (for Trisomy 18), there are some medical things that we can do to help support their body,” said Dr. Lindsay Ragsdale, director of PACT. “Most people think palliative care is end-of-life care, but really, it’s about kids with serious illness and how we help them live each day the best they can. So, it’s really about living.”

Duerson said they tried to prepare themselves for every possibility leading up to Wylie’s birth. “I just tried to enjoy her life inside of me, not knowing how long she would be with us,” she said, explaining that they didn’t even buy a crib; they had been mentally preparing to bury her. But Wylie’s birth, by scheduled c-section, shocked them all.

“[W]hen they showed her to me, she was awfully floppy and blue. She didn’t look like a baby who was alive,” Duerson said. “But they let my husband hold her, and I will never forget the moment. I’d just given birth and he just says, ‘She’s breathing Karla, she’s breathing!’ And she just kept breathing and kept living.”

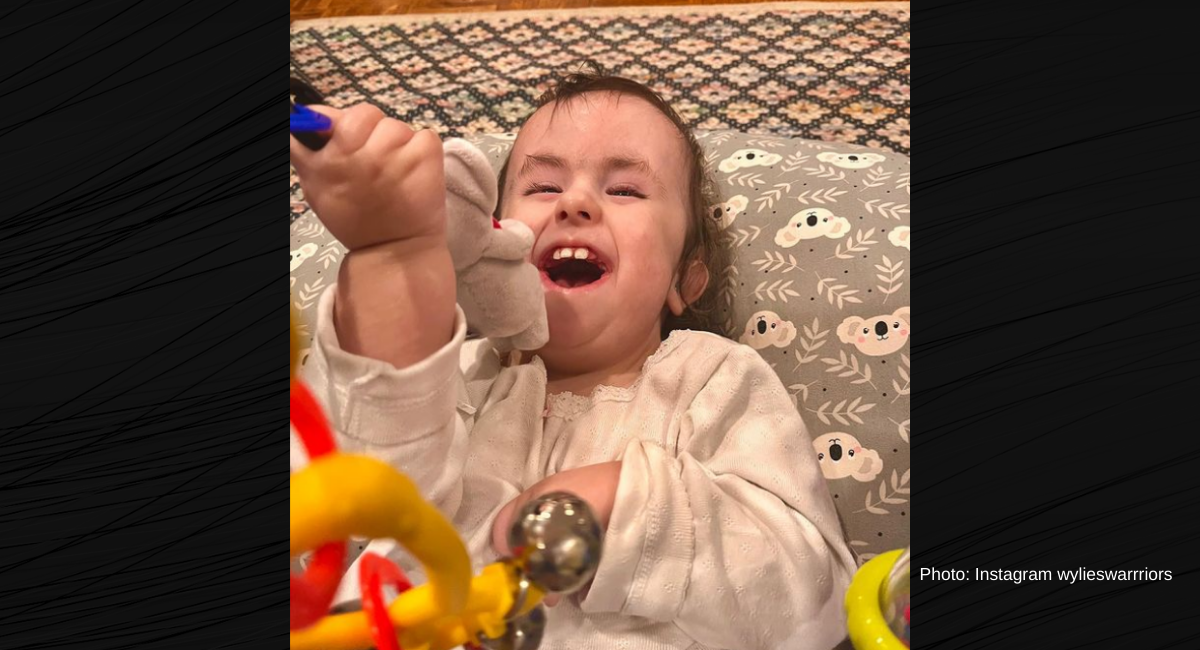

Wylie was put on a feeding tube, but she didn’t need to be placed on supplemental oxygen; she kept breathing on her own. By three months old, she successfully underwent open-heart surgery. Wylie will be three in May and continues to blaze a trail — not just for her, but for other babies with Trisomy 18, too.

“I remember Dr. Ragsdale saying, ‘We are going to see what Wylie tells us. What Wylie tells us she needs, we’re going to give her that,’” Duerson said. “And Gavin and I were just like, ‘Is this real? This is exactly what we want to hear, but is it real? Can this really happen?’ And it did. Wylie can communicate her needs, and they really did respond to her — not just to their preconceived notions about a baby with Trisomy 18.”

The seemingly simple approach of looking at what Wylie needed and giving it to her has not been the norm for children with Trisomy 18. Now, it’s being called the Wylie Way.

“All the other patients who have had Trisomy 18 that have come behind Wylie — she kind of has helped forge some of those paths for us,” Ragsdale said. “This was kind of a new horizon for us to say, yeah, we should be offering more surgeries and more options for Trisomy 18. I think every children’s hospital over the past 10 years has had this shift and it’s usually because they’ve had patients really change how they’ve done things. Wylie is cited by multiple professionals. We’ll say, ‘Let’s do it the Wylie way and see how it works.’”

“Like” Live Action News on Facebook for more pro-life news and commentary!