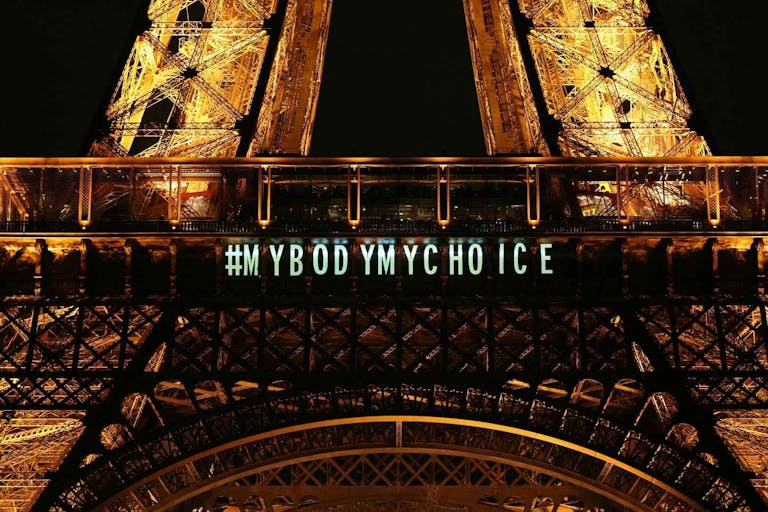

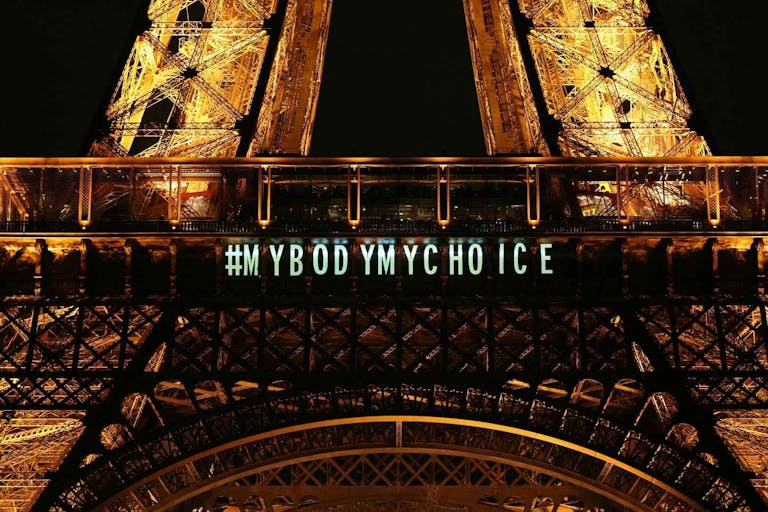

France exonerates all women penalized for abortion before its legalization

Angeline Tan

·

Clinic worker quits, calls her former workplace an “abortion mill”

Dina Madsen began working at a Sacramento abortion clinic (which she would later describe as an “abortion mill”) in 1990. According to her, she had been living a “dysfunctional” life and knew little about abortion when she took the job.

In testimony that Madsen gave at a Pro-Life Action League conference (an excerpt of which can be found here), Madsen said she had no medical background when she began working at the clinic. Medical experience and training were not required for a position on the abortion clinic staff. The only thing that was required, Madsen said, was “a positive opinion towards abortion.”

Madsen described the pro-choice views she held when she became an abortion clinic worker:

I had a couple friends in high school who had had abortions, and I had a pregnancy scare myself when I was an adolescent; that was the first thing that came to my mind. I never thought about having the baby. I just took it as the general consensus, the general population does, that it is a choice. Unfortunately, it’s often presented as the only choice.

So Madsen had no problem going to work at the clinic. One thing she noticed quickly, however, was that the other clinic workers did not have much faith in the doctors they worked with.

And of all the women I worked with, several of those women, at least half of them, had had abortions and had repeat abortions. And yet they wouldn’t let any of these guys [abortionists] touch them with a 10-foot pole. Never. And yet every day they told these other women, “They’re wonderful doctors, they won’t hurt you. They’re the best at what they do. He’s really a nice man.” And sometimes the women would ask, “Have you ever had an abortion?”And of course they wouldn’t say, “Yes, but not by him.”

In her testimony, Madsen described rudeness and incompetence among the clinic’s abortionists and maintained that the clinic workers were well aware that their doctors were substandard. Madsen eventually came to have contempt for the women she was supposed to be helping. She admitted in her testimony:

I have to admit, though, I didn’t really have much sympathy for them [the women]. In my view, well, you got yourself into this position. Tough it out.

Madsen describes how many of the clinic workers had previous abortions. In another part of her testimony she says, “Some of the directors I worked with had eight or nine abortions[.]”

Other former clinic workers have also mentioned that many people they worked with had had previous abortions; some former clinic workers have said they had abortions themselves. David Reardon, president of The Elliot Institute, which works with post-abortion women and conducts research on abortion’s emotional aftereffects, speculated as to why post-abortion women might decide to work in abortion clinics:

Aborted women who work as [abortion] counselors are almost invariably victims of a disturbing abortion experience themselves. On one level, they choose to work in clinics in the hope of preventing other women from experiencing the traumas which they had faced and may still be facing. But on a deeper level, they returned to the abortion clinic in the hope of easing the guilt and traumas which they themselves are still experiencing.

For many women who have been deeply disturbed by their own abortion experiences, working as an abortion counselor’s a way of hardening themselves. … By “returning to the scene of the crime,” some women seek to reenact their own abortion decisions through the decisions of others. In this sense, the aborted counselor has a high stake in the final decision of her clients. By watching others choose abortion for the same reasons that she did, she is able to reaffirm the “rightness” of her own decision. In contrast, however, when an aborted counselor witnesses a client suddenly choose against abortion and boldly accept the challenges of an unplanned pregnancy, the counselor may become cynical, ashamed, and envious.

If David Reardon is right, and abortion clinic workers sometimes have an emotional stake in convincing a woman to have abortions, it might explain why the counseling at many abortion clinics is misleading or coercive.

Reardon goes on to say:

Article continues below

Dear Reader,

In 2026, Live Action is heading straight where the battle is fiercest: college campuses.

We have a bold initiative to establish 100 Live Action campus chapters within the next year, and your partnership will make it a success!

Your support today will help train and equip young leaders, bring Live Action’s educational content into academic environments, host on-campus events and debates, and empower students to challenge the pro-abortion status quo with truth and compassion.

Invest in pro-life grassroots outreach and cultural formation with your DOUBLED year-end gift!

Two WEBA [Women Exploited by Abortion, a group of pro-life postabortive women] women who had worked in counseling or hospital situations that brought them into contact with women seeking abortions have described how immersion in abortion can be soothing to troubled conscience. According to one, “I found that in talking to other women about abortion, their decisions to abort satisfied something in me. It made me feel better about what I had done… [It] strengthened my own decisions to abort.”

Another woman found comfort in being surrounded by people constantly repeating pro-abortion rhetoric as justification for their work: “there’s safety in numbers. I didn’t really feel awful about my abortion as long as everyone where I worked was patting me on the back.” (1)

Many of the women coming to the clinic had had multiple abortions, too. According to Madsen:

And every time she’d come in for an abortion or a D&E [late-term abortion – see details here], we’d stamp, stamp, stamp, stamp – some of these charts were filled in on both sides. And the doctor would take a look at them and say, “Gee, if she tries real hard, she can come in again before Christmas.” And this is somebody who cares about women? I don’t think so.

Madsen described answering the phone and talking to women seeking abortions:

A woman would call, and I’d make her feel that this was her choice and that we were going to support her in this choice. Because the women are looking for someone to support their decision.

Many of the women may have been looking for someone who would support their decision – but others might have been confused and uncertain about what to do about their pregnancies. One survey showed that up to 41% of abortion-seeking women were ambivalent about their choice. Incredibly, in the same survey, only 29% of women said they were truly “happy with their decision” at the time of their abortions. Forty-four percent said they were still actively looking for another option right up until the moment they were on the abortion table and about to have surgery.

Madsen summed up her work at the clinic the following way:

My official title at the mill was “health worker.” I did various duties – lab work, leading groups (deceiving women about their abortions), “advocating” (deceiving women during their abortions), and assisting the abortionist, which included helping during the abortion and checking to make sure all the parts of the baby were there in the collection jar afterwards. I will never forget, in the second-trimester abortions, holding those little feet up to a chart on the wall to make sure of the age of the baby.

She said that she had had no regard for the lives of unborn babies, and, ultimately, no regard for life in general:

… I was looking at these babies as something to be disposed of. I didn’t see them as important, I didn’t see life as important, I didn’t value my own life, therefore how can I value anyone else’s life. And if these women were stupid enough to get pregnant, then it was their fault. And that’s how I felt. And that was how the majority of the staff felt.

Eventually, though, the efforts of pro-lifers to reach the clinic workers and women had an impact on Madsen:

Just like everyone else employed there, I laughed at the pro-lifers outside the mill and hardened my heart against the truth. If I thought about what was really happening, it became overwhelming. So I treated the whole issue as a joke – but somewhere along the line God started working on my heart. I started to read literature left by the pro-lifers, and pro-life books. I began to see what I was doing in a whole new light. I saw these babies for what they were – human beings. It was very hard for my heart and head to accept because I had been leaving both my heart and head at home for so long to work there.

Pro-lifers who try to reach out to clinic workers and abortion-minded women at clinics never know what impact they will have. They may not see the fruits of their efforts for a very long time, if ever. But if these pro-lifers outside Madsen’s “abortion mill” had not been persistent in distributing their literature, Madsen may never have read it and then sought out pro-life books to read. She may never have had her conversion. In this case, as in many others, faithfully communicating the pro-life message paid off. Like water dripping on stone, the pro-life message, spread with compassion and persistence, can soften the hardest hearts.

More of Dina Madsen’s story, and commentary by father Frank Pavone, can be found here on the Priests for Life website.

1. David C Reardon, Aborted Women: Silent No More (Westchester, Illinois: Crossway books, 1987), 256.

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Angeline Tan

·

Politics

Cassy Cooke

·

Guest Column

Right to Life UK

·

Issues

Angeline Tan

·

Issues

Bridget Sielicki

·

Issues

Nancy Flanders

·

Guest Column

Sarah Terzo

·

Abortion Pill

Sarah Terzo

·

Guest Column

Sarah Terzo

·

Guest Column

Sarah Terzo

·

Guest Column

Sarah Terzo

·