Last month, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), claiming that the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Systems (REMS) safety requirements regarding the use of the abortion pill would put patients’ lives at risk during COVID-19. However, the FDA has chosen to fight back and stand by its safety requirements, calling the lawsuit’s assertions about risking patients’ lives “speculative” at best.

As previously reported by Live Action News, Eva Chalas, MD, FACOG, FACS, and president of ACOG, stated that:

… [T]he federal government should permit patients seeking safe and effective reproductive health care, which includes care for miscarriage and termination of pregnancy, the same ability to access care and protect themselves from exposure as patients in other contexts are afforded.

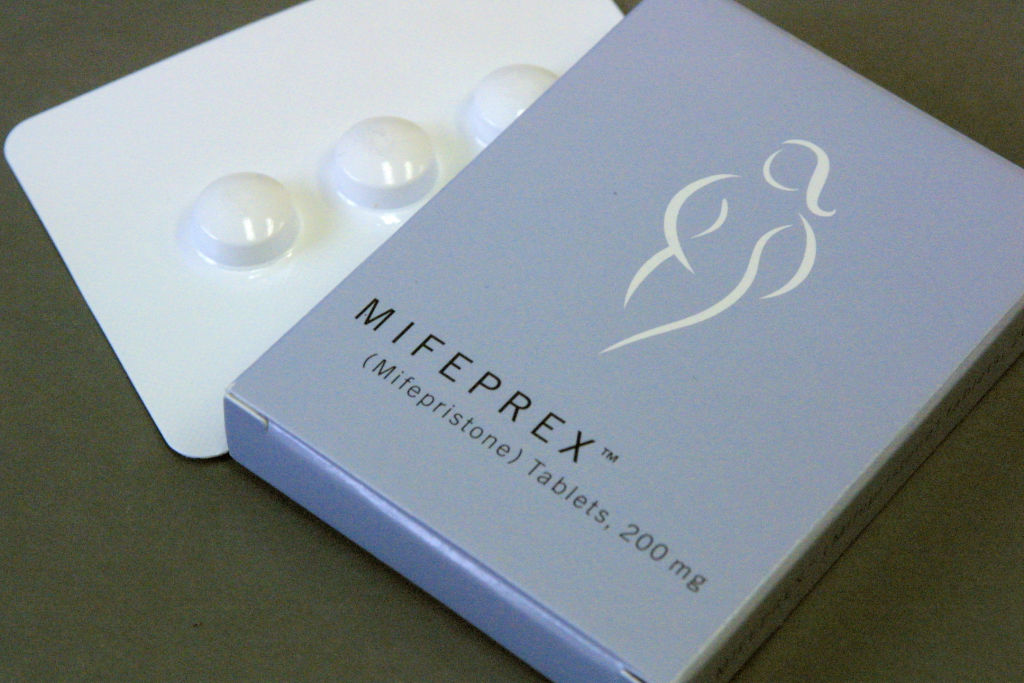

Yet, the FDA, according to Bloomberg Law, explained that “the in-person dispensing requirement addresses serious health risks associated with mifepristone.” Some of these risks include “incomplete abortion and serious bleeding requiring surgical intervention in up to seven percent of women who take the drug,” as seen in the FDA’s brief from Wednesday.

The FDA’s brief then notes that “plaintiffs have not shown that adhering to the in-person dispensing requirement during the COVID-19 pandemic poses a substantial obstacle to a large fraction of women seeking an abortion, much less that it is invalid in all circumstances.” The FDA explains that, on top of the speculative risk of exposure to COVID-19, the demographic of women that would be using the drug would be below age 50 and therefore excluded from the high-risk category for the virus.

The ACLU/ACOG lawsuit claims that the FDA’s abortion pill safety requirements “impose[] an undue burden” on women. The FDA disagrees. The brief states:

Their due process claim—that the in-person dispensing requirement imposes an undue burden on their patients’ ability to obtain an abortion— fails for numerous reasons, including that there is no substantive due process right to use this particular drug to obtain an abortion. FDA did not even approve Mifeprex until 2000, and there could have been no claim prior to that date that its absence imposed a substantial obstacle to obtaining an abortion.

In its brief, the FDA also – perhaps unintentionally – exposes the fallacious idea that a woman’s decision to abort is “between a woman and her doctor” by noting that the abortion industry has no “close relationships” with its clients:

Furthermore, Mifeprex prescribers are not entitled to assert the rights of patients. They fail to show that they have the sort of close relationship with patients necessary to establish third-party standing. Indeed, the entire point of this suit is to reduce plaintiffs’ relationship with patients to electronic interactions and mail. Even if plaintiffs could surmount these hurdles, they still have not established a likelihood of success on their claims.

Indeed, it is a conflict of interest to allow parties who would profit from the expansion and unrestricted use of the abortion pill to bring lawsuits that purport to be on behalf of abortion clients. But then, conflict of interest plays a large role in many other aspects of the abortion and abortion pill industry, especially when it comes to funding and clinical studies.

As the lawsuit continues, some states—including Indiana, Louisiana, Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, and Oklahoma—have asked to join in the FDA’s defense of REMS and have opposed the ACOG’s attempt to increase access to the dangerous abortion pill.

Editor’s Note: For information on how to potentially reverse the effects of the abortion pill, visit AbortionPillRescue.com.

“Like” Live Action News on Facebook for more pro-life news and commentary!