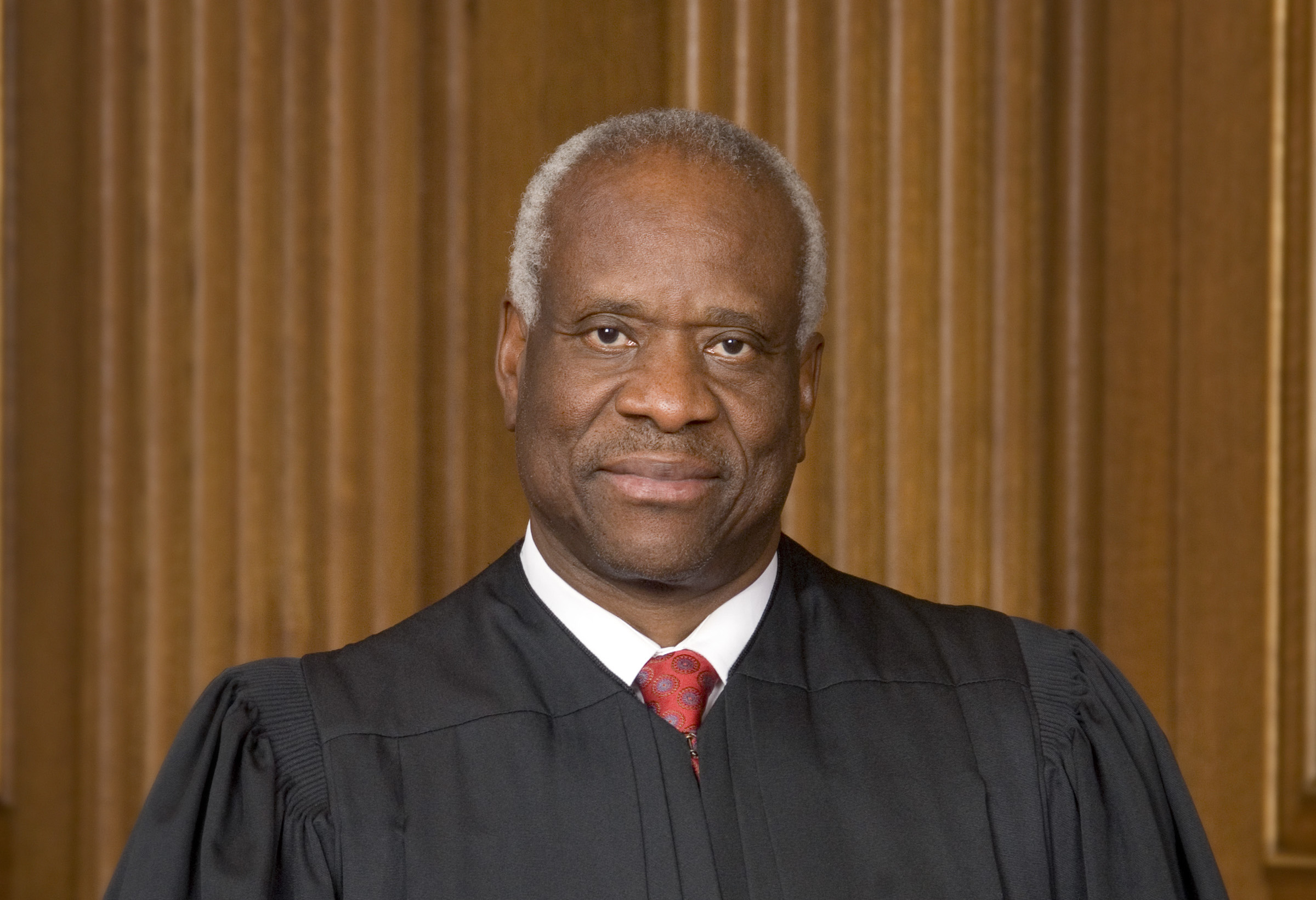

Twenty-five years ago Sunday, Justice Clarence Thomas took his place on the United States Supreme Court. With the passing of Justice Antonin Scalia in February, Thomas is now the most committed champion for the Constitution and the right to life remaining at the top of the federal judiciary.

In 2001, Thomas laid out the essence of his judicial philosophy in a speech to the American Enterprise Institute. He started with a simple truth: that while “reasonable minds often differ” on the exact meaning of certain constitutional provisions, “that does not mean that there is no correct answer, that there are no clear, eternal principles recognized and put into motion by our founding documents […] The law is not a matter of purely personal opinion.”

From these starting principles, there was only one conclusion Thomas could draw about the raw exercise of judicial malpractice that is legalized abortion-on-demand.

In 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey, Thomas joined Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s dissenting opinion “that Roe was wrongly decided, and that it can and should be overruled consistently with our traditional approach to stare decisis in constitutional cases, as well as Scalia’s opinion “that a woman’s decision to abort her unborn child is not a constitutionally protected ‘liberty,’ because (1) the Constitution says absolutely nothing about it, and (2) the longstanding traditions of American society have permitted it to be legally proscribed.”

In 2000’s Stenberg v. Carhart ruling upholding the “right” to partial-birth abortion, Thomas wrote a dissenting opinion blasting the majority for not only disregarding the Constitution’s plain meaning, but for interpreting the fraudulent “health exceptions” loophole even more broadly than Casey itself required:

In effect, no regulation of abortion procedures is permitted because there will always be some support for a procedure and there will always be some doctors who conclude that the procedure is preferable. If Nebraska reenacts its partial birth abortion ban with a health exception, the State will not be able to prevent physicians like Dr. Carhart from using partial birth abortion as a routine abortion procedure […] The majority’s insistence on a health exception is a fig leaf barely covering its hostility to any abortion regulation by the States–a hostility that Casey purported to reject.

He also shamed the majority for misrepresenting what partial-birth abortion really is:

In the almost 30 years since Roe, this Court has never described the various methods of aborting a second- or third-trimester fetus. From reading the majority’s sanitized description, one would think that this case involves state regulation of a widely accepted routine medical procedure. Nothing could be further from the truth. The most widely used method of abortion during this stage of pregnancy is so gruesome that its use can be traumatic even for the physicians and medical staff who perform it.

In 2007’s Gonzales v. Carhart, which finally upheld the federal partial-birth abortion ban, Thomas wrote a concurring opinion that affirmed the majority’s judgment, but reiterated his contention that the entire judicial regime propping up the “right to choose” needs to go: “the Court’s abortion jurisprudence, including Casey and Roe v. Wade, 410 U. S. 113 (1973), has no basis in the Constitution.”

He also, of course, voted with the majority in 2014’s Burwell v. Hobby Lobby to uphold private entities’ constitutional right to not provide abortifacient drugs against their will.

Most recently, Thomas powerfully dissented from the Supreme Court’s Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, which all but eviscerated states’ rights to place basic health and safety regulations on abortion facilities. He chastised the majority for “second-guessing medical evidence and making its own assessments of ‘quality of care’ issues,” thereby “reappoint[ing] this Court as ‘the country’s ex officio medical board.”

He stated the high court used “empty words” to impose its will by “judicial fiat,” “transform[ing] judicially created rights like the right to abortion into preferred constitutional rights, while disfavoring many of the rights actually enumerated in the Constitution” and “using ‘made-up tests’ to ‘displace longstanding national traditions as the primary determinant of what the Constitution means.’”

Thomas boiled down the essence of the problem with a grim warning for the nation:

Today’s decision will prompt some to claim victory, just as it will stiffen opponents’ will to object. But the entire Nation has lost something essential. The majority’s embrace of a jurisprudence of rights-specific exceptions and balancing tests is ‘a regrettable concession of defeat—an acknowledgement that we have passed the point where “law,” properly speaking, has any further application.

Thomas has long held to the original intent of the Constitution:

When interpreting the Constitution and statutes, judges should seek the original understanding of the provision’s text, if the meaning of that text is not readily apparent.

This approach works in several ways to reduce judicial discretion and to maintain judicial impartiality. First, by tethering their analysis to the understanding of those who drafted and ratified the text, modern judges are prevented from substituting their own preferences for the Constitution.

Second, it places the authority for creating the legal rules in the hands of the people and their representatives, rather than in the hands of the judiciary. The Constitution means what the delegates of the Philadelphia Convention and of the state ratifying conventions understood it to mean; not what we judges think it should mean.

Third, this approach recognizes the basic principle of a written Constitution. “We the people” adopted a written Constitution precisely because it has a fixed meaning, a meaning that does not change. Otherwise we would have adopted the British approach of an unwritten, evolving constitution. Aside from amendment according to Article V, the Constitution’s meaning cannot be updated, or changed, or altered by the Supreme Court, the Congress, or the President.

This is only legitimate way to operate a judiciary in a governing system like America’s. The entire point of having a written Constitution is that there are things neither a majority nor a minority should be able to do to each other, boundaries enforced by a normally immutable standard that is as divorced as humanly possible from policy preferences or value judgments.

The fact that abortion advocates, however, lay out a judicial philosophy fixated entirely on subjective value judgments is their first tell that they only believe in manipulating the law to get whatever outcomes they want.

To decide cases based on anything beyond what Thomas describes above defeats the Supreme Court’s very purpose in impartially holding all parties to that standard. Indeed, the fact that justices didn’t have that discretion was supposed to be why we could trust them with unelected positions and lifetime tenure.

For two-and-a-half decades, Clarence Thomas has been one of the pro-life movement’s truest friends in Washington, D.C. And yet, he’s done so not by imposing his personal will on the law in the opposite direction (i.e., claiming the Constitution forces states to ban abortion), but by simply following the letter of the law and standing up for our right as Americans to answer the question for ourselves through the democratic process.

Here’s hoping that Clarence Thomas remains on the Supreme Court for years to come.