She chose life for her children, no matter what the future might hold

Melina Nicole

·

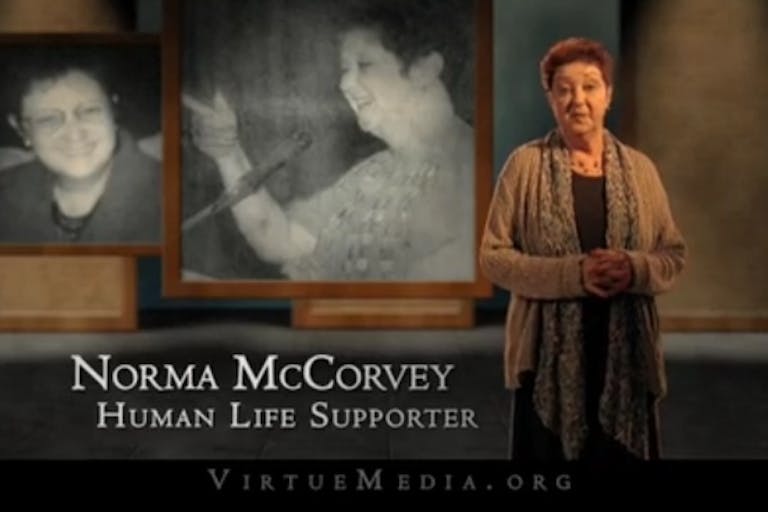

‘Roe’ of Roe v. Wade: Abortionists lie, women suffer, and babies die

Norma McCorvey was the plaintiff in the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, which forced legal abortion throughout the country. Few people know that she also worked in abortion clinics before becoming pro-life.

In her sworn deposition (Norma McCorvey, also known as “Jane Roe” of Roe v. Wade) of March 15, 2000 (which can be found in its entirety here) she describes some of the experiences she had while working in the abortion industry.

No matter how hard McCorvey’s clinics tried to hide the truth about abortion from women, they were unable to. McCorvey tells the following heartbreaking story:

The doctors always hid the truth from the mothers. …Specifically, I remember one woman who came in for an abortion, a pretty, sweet young woman about eighteen years old, with a teddy bear. During the procedure she looked down and saw the baby’s hand fall into the doctor’s hand. She gasped and passed out.

When she awoke and asked about what she saw, I lied to her and told her it didn’t happen. But she insisted that she had seen part of her baby. A few weeks later, when she returned for her follow-up exam, she was a changed person: her sweetness had died and had been replaced with an indescribable hardness. I could not look her in the eye. It took quite a few beers that night to make that particular day go away. In all of the clinics I worked in the employees were forbidden to say anything that could talk the mother out of an abortion.

McCorvey talked about the “counseling” that women received in the clinics.

While the manners of the abortionists and the uncleanliness of the facilities greatly shocked me, the lack of counseling provided the women was perhaps the greatest tragedy. Early in my abortion career, it became evident that the “counselors” and the abortionists were there for only one reason – to sell abortions.

The extent of the abortionists’ counseling was, “Do you want an abortion? Ok, you sign here and we give you abortion.” [sic]. Then he would direct me, “You go get me another one.” There was nothing more. There was never an explanation of the procedure.

No one even explained to the mother that the child already existed and the life of a human was being terminated. No one ever explained that there were options to abortion, that financial help was available, or that the child was a unique and irreplaceable.

No one ever explained that there were psychological and physical risks of harm to the mother. There was never time for the mother to reflect or to consult with anyone who could offer her help or an alternative. There was no informed consent. In my opinion, the only thing the abortion doctors and clinics cared about was making money. No abortion clinic cared about the women involved. As far as I could tell, every woman had the name of Jane Roe.

McCorvey describes women struggling on their own to resolve the moral dilemma of abortion with no help from the clinic workers. The woman received no counseling and no information about the preborn baby, or about their other options. They were not told anything that could help them carry the pregnancy to term. While it is definitely not surprising that the clinic workers would refuse to give any information that might lead to a woman changing her mind – after all, abortion clinics can only stay open and pay their staff if they sell abortions – the sense that the women were nameless and faceless, only valued as far as they brought income to the clinic, is a bleak and sad picture.

Planned Parenthood and other pro-abortion groups spend millions of dollars fighting informed consent laws that would require abortion clinics to give a more balanced picture of abortion to women. Even though informed consent laws cannot force clinic workers to be fair and unbiased, they can at least make sure women are given vital information that may allow them to make an informed decision. It is hard to understand why a woman would be harmed by being told about resources in the community that could help her choose life or about the medical risks of abortion.

Pro-abortion groups will say that women who come to an abortion clinic have already made up their mind, but research indicates that may not always be true.

According to a survey published in David Reardon’s book Aborted Women: Silent No More, 40 to 60 percent of post-abortion women surveyed described themselves as not having been certain of their decision prior to arriving at the abortion clinic, and undergoing whatever counseling they offered. Forty-four percent stated they were actively hoping to find an option other than abortion during counseling. Because Reardon’s survey sample consisted mainly of women who regretted their abortions, the actual numbers may be lower. But regardless of what the actual percentage is, it is clear that some women who come to abortion clinics could benefit from counseling, or at least from being given information about options and resources in the community.

In the same survey, 90 percent of respondents said they were not given enough information to make an informed decision. Although McCorvey did not work in a Planned Parenthood clinic, it should be noted that:

95% of women who had abortions at Planned Parenthood said that their Planned Parenthood counselors gave “…little or no biological information about the fetus which the abortion would destroy.”

McCorvey found herself rebelling against the clinic rules that prohibited her from saying anything that might discourage a woman from having an abortion. Struggling with a drug and alcohol addictions, McCorvey counseled women differently depending on her mood:

The experience of abortion began to take its toll on me. While the abortionists’ counseling was non- existent, my counseling technique gradually became different depending on my mood and the stage of my career. In later years, I would sometimes take all the instruments that were used in an abortion procedure and purposely leave a little of the blood on some the instruments.

Laying the instruments out on the little table in front of the woman, I would tell her that, “This is the first instrument that is going to be inserted into your vaginal area.” It would have just had a little smudge of blood, and I thought it was very dramatic. In retrospect, I don’t even know why I was doing these things. It was as if I was trying to talk these women out of the abortion– something we were forbidden to do.

In other counseling sessions, I would demonstrate the position and warn her that the instruments were sharp, and that if she moved the doctor might slip, and puncture her uterus, and she would bleed to death. In other situations, when a woman asked me how much it cost, I asked her in response how much she wanted to pay to kill her baby. She replied, “They told me it wasn’t a baby.” I responded, “What do you think it is inside you, a fish?” Other times I would comfort them after the abortion by saying, “It wasn’t a baby. It was only a missed period.” Sometimes when I managed to make the women unsure, I would offer to refund their money except for the ultrasound.

McCorvey speaks even more bluntly about how she felt working in the clinic:

After I saw all the deception going on in the abortion facilities, and after all the things that my supervisors told me to tell the women, I became very angry. I saw women being lied to, openly, and I was part of it. There’s no telling how many children I helped kill while their mothers dug their nails into me and listened to my warning, “Whatever you do, don’t move!”

She dealt with the guilt by drinking heavily:

Because I was drunk or stoned much of the time, I was able to continue this work for a long time, probably much longer than most clinic workers. It is a high turnover job, because of the true nature of the business. The abortion business is an inherently dehumanizing one. A person has to let her heart and soul die or go numb to stay in practice. The clinic workers suffer, the women suffer, and the babies die.

McCorvey explains how the doctors in her clinics were primarily concerned with the monetary rewards of performing abortions:

While all the facilities [I worked in] were much the same, the abortion doctors in the various clinics where I worked were very representative of abortionists in general. The abortionists I knew were usually of foreign descent with the perception that the lax abortion laws in the United States present a fertile money-making opportunity. One abortionist, in particular, would sometimes operate bare-chested, and sometimes shoe less with his shirt off, and earned a six-figure income. He did not have to worry about his bedside manner, learning to speak English, or building a clientele.

In these cases, the abortionists were not working at the clinics out of an altruistic desire to help women or even a commitment to the pro-choice cause. Rather, they saw an opportunity to make money and seized it.

McCorvey’s testimony reveals the true horror of working in an abortion clinic. The daily deception clinic workers witness and are expected to take part in and seeing the bodies of aborted babies daily take a huge toll on clinic workers.

The true victims of abortion, of course, are the baby and the mother, who is forced to carry the burden of her abortion for the rest of her life. But we must not forget the clinic workers are also human beings with emotions who are involved in, in McCorvey’s words, a “bloody and dehumanizing business.” Just like the baby and the mother, they deserve our compassion.

Nothing but compassion can lead clinic workers out of the abortion industry, and nothing but compassion can help them heal afterwards.

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Melina Nicole

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Abortion Pill

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Nancy Flanders

·

Guest Column

Sarah Terzo

·

Abortion Pill

Sarah Terzo

·

Guest Column

Sarah Terzo

·

Guest Column

Sarah Terzo

·

Guest Column

Sarah Terzo

·