Investigative

Former Planned Parenthood staffer describes how women were coerced and misled

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative·By Carole Novielli

Not just Nazis: The grisly history of research on abortion survivors

A look back at some of the grisly experiments once conducted on human abortion survivors will most likely make your stomach turn. This history shows the depravity a society can spiral into when medical research is allowed to advance untethered to any sense of ethical morality. Today, as videos of Planned Parenthood staffers haggling over the price of aborted baby body parts come to mind, a look into the fetal research market dating back to the 1930s reveals again how those who experiment on the bodies of tiny victims will often justify their actions as good.

Davenport Hooker’s Fetal Experiments on Living Aborted Babies

From the 1930s until the mid 1960s, University of Pittsburgh anatomist Davenport Hooker conducted research on children who survived surgical abortion by hysterotomy, a risky procedure similar to Caesarian section, where the doctor opens up the uterus with an incision and pulls the baby out.

Forensic anthropologist Emily K. Wilson authored a paper in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, explaining how Hooker obtained the abortion survivors:

Immediately following a surgical abortion by hysterotomy, performed on an unnamed woman at a nearby lying-in hospital, Hooker took the seven-week-old fetus to an observation room. He touched and stroked the face, body, arms, and legs as a motion picture camera recorded the fetus’s corresponding movements and reflexes. Over the next thirty-one years, Hooker would observe more than 150 fetuses and prematurely born infants in this manner. The project resulted in over forty articles and one nine-minute medical film and contributed information and photographic stills to numerous scientific and popular publications.

Wilson also writes, “But while Hooker and the 1930s medical and general public viewed live fetuses as acceptable materials for nontherapeutic research, they also shared a regard for fetuses as developing humans with some degree of social value.”

READ: New research on amniotic fluid is latest proof we don’t need fetal tissue

According to PittMed, a publication of the University of Pittsburgh, “Hooker purchased a 35-mm motion picture camera. Having gained the trust and permission of the obstetricians at Magee-Womens Hospital, Hooker was able to observe therapeutically aborted fetuses removed by Caesarian section. Upon stimulating the skin, he recorded the degree of reflex development, and in January of 1933, created the first films ever made of human fetal movement.”

Rutgers professor Johanna Schoen, an abortion supporter, adds, “In 1952, he [Hooker] assembled his footage into a silent educational film called “Early Fetal Human Activity.” The film showed the muscle activity of six fetuses ranging from 8 1/2 to 14 weeks.”

Video from that film can be viewed below (Warning – Images may be disturbing for some):

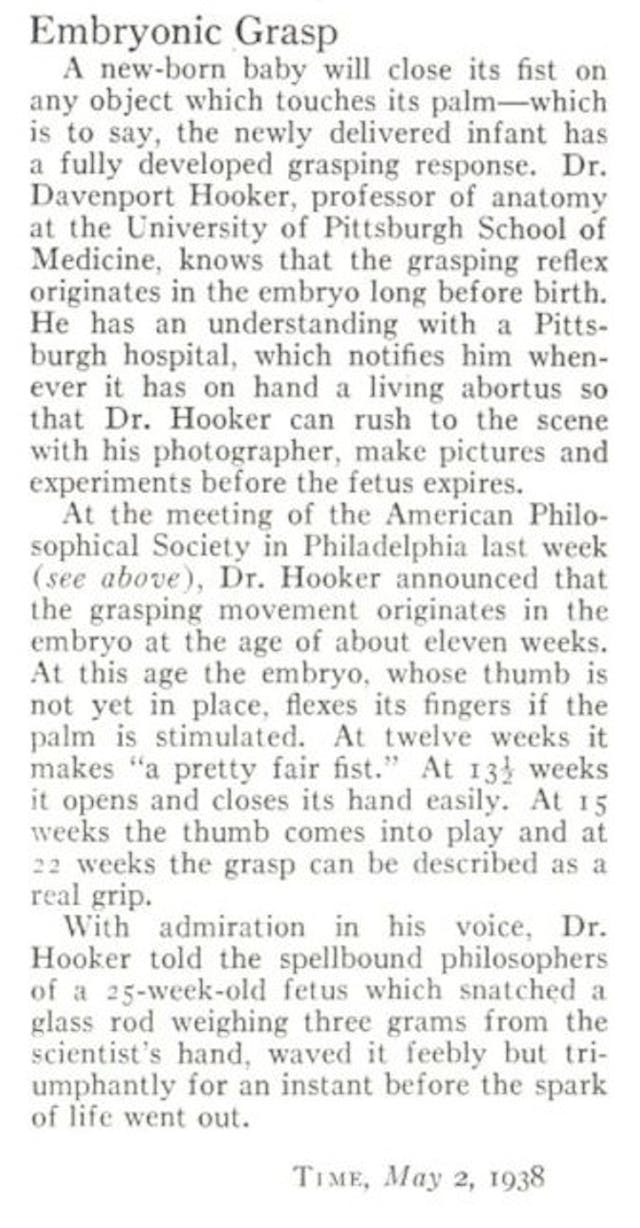

Author Lynn Morgan also did research on Hooker and discovered a brief account of Hooker’s experiments before the American Philosophical Society were published in a 1938 Time Magazine article entitled, “Embryonic Grasp.” Morgan writes:

“It described how a twenty-five week old fetus “snatched a glass rod weighing three grams from the scientist’s hand, waved it feebly but triumphantly for an instant before the spark of life went out.”

Hooker pointed out to his audience that an abortion survivor at twelve weeks gestation makes a “pretty fair fist.”

The article noted that the doctor was notified by a Pittsburgh hospital, “whenever it has on hand a living abortus so that Dr. Hooker can rush to the scene with his photographer, make pictures and experiments before the fetus expires.”

Writing in her book, “Icons of Life: A Cultural History of Human Embryos,” Morgan seemed troubled by the calloused demeanor of Hooker’s audience and the journalist, writing:

“The journalist cited the “admiring voice” of the scientist as Hooker described his findings before a “spell bound” audience… Didn’t the audience question the ethics of fetal experimentation? Didn’t the audience question whether 149 women would have had to be subjected to major abdominal surgery if the researchers had not wanted the fetuses delivered alive?”

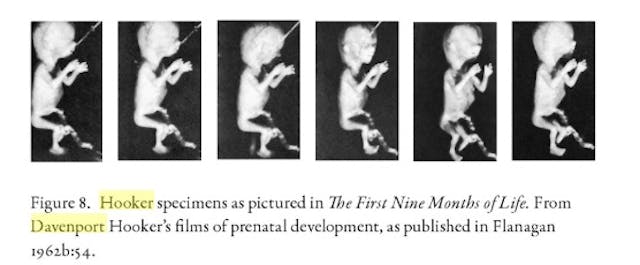

Schoen, who approves of using abortion survivors for research, goes on to write that, “Several of Hooker’s images were published in 1962 in an early pregnancy guidebook, ‘The First Nine Months of Life.’ Its author, Geraldine Flanagan, did not discuss how the fetuses were photographed or mention the conditions, such as therapeutic abortion, that allowed them to be used in research.”

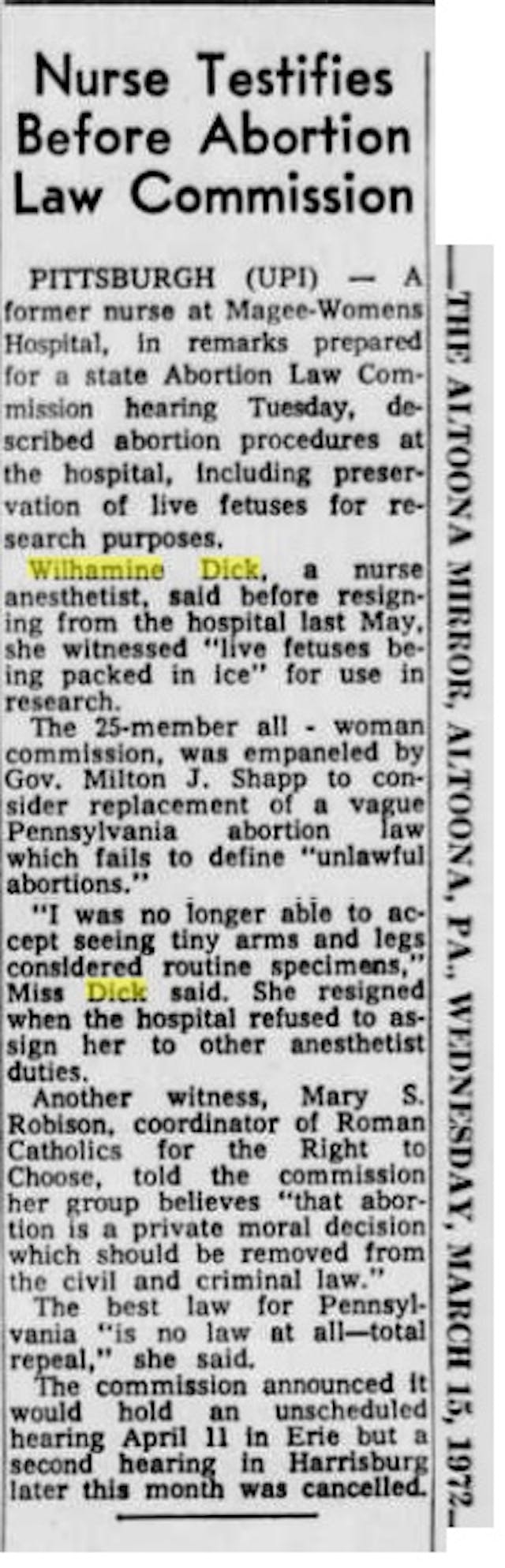

Nurse Testifies Aborted Fetuses Shipped Alive on Ice

In 1972, a former Magee-Women’s Hospital nurse anesthetist testified before the Pennsylvania Abortion Law Commission that she witnessed the hospital shipping aborted and still living human fetuses to researchers for experimentation. Wilhamine Dick told the committee she witnessed “live fetuses being packed on ice” for use in research. According to a March 15, 1972, article published by the Indiana Evening Gazette, the former nurse also told the commission, “It was repulsive to watch live fetuses being packed in ice while still moving and trying to breathe, then being rushed to some laboratory and hear the medical students later discuss the experience of examining the organs of a once live baby.” She added that she resigned because she was “no longer able to accept seeing tiny arms and legs considered routine specimens.”

Stanford University Experiments on Living Aborted Children

Article continues below

Dear Reader,

Have you ever wanted to share the miracle of human development with little ones? Live Action is proud to present the "Baby Olivia" board book, which presents the content of Live Action's "Baby Olivia" fetal development video in a fun, new format. It's perfect for helping little minds understand the complex and beautiful process of human development in the womb.

Receive our brand new Baby Olivia board book when you give a one-time gift of $30 or more (or begin a new monthly gift of $15 or more).

A report by the New York Times detailed experiments which involved scientists at Stanford University who allegedly immersed 15 abortion survivors in a salt solution to see if they could absorb oxygen through the skin. An October 4, 1973, report by the Placerville Mountain Democrat quoted an alleged witness by the name of James Babcock, who told a legislative panel that he “learned that live fetuses had been placed in a special chamber, their ribs cut open to observe their heartbeat under certain conditions.”

A report by the Stanford Daily, which did not dispute that the experiments happened, claimed the project had been “terminated in 1969.” In fact, according to the report, Dr. Robert Goodlin, an associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics, performed the research at Stanford in the 1960s and told the paper, “Our goal was to keep the fetus alive.” He added, “Cutting the fetus open was sometimes necessary to observe heart action and at other times to massage the heart.”

Paul Ramsey, author of “The Ethics of Fetal Research,”writes that the longest Goodlin was able to keep a fetus alive was eleven days, adding, “Again, the experiments would have been pointless if those previable abortuses had not been importantly and relevantly ‘alive’ before yet having capacity for respiration.”

The Stanford Daily reported, “Funds for further research were halted in 1969 when it was decided that Goodlin and other scientists were ‘too far away’ from their goal of keeping the fetus alive outside the womb….”

The paper also stated:

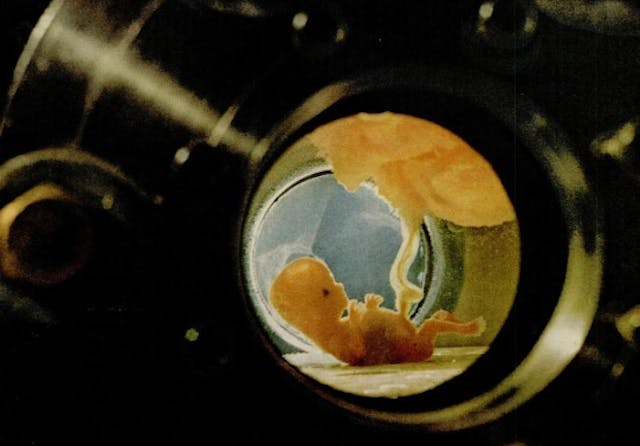

Stanford, along with other medical schools in the nation, made their research widely known in Life magazine article in September, 1965. Life stated that Goodlin and other scientists were “working toward the day when it would become routine to save prematurely

aborted fetuses at almost any age and carry them through to “birth” in artificial wombs.… In 1965, Life magazine depicted a 10-week-old fetus kept alive in an artificial womb by Goodlin’s team of Stanford physicians. Goodlin said the objective at all times was “to preserve life.”

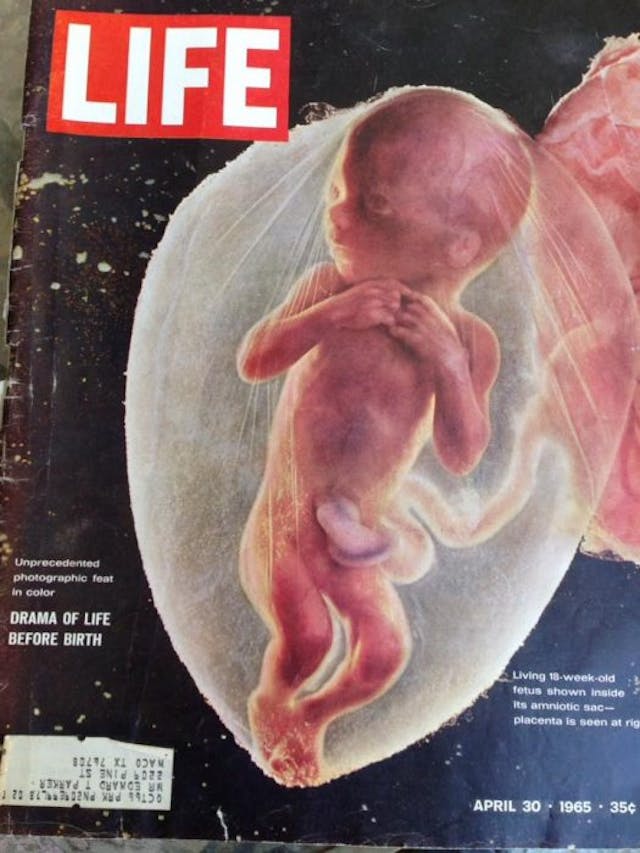

That same year, Life Magazine published Swedish photographer Lennart Nilsson’s photo essay, “Drama of Life Before Birth.” Nilsson later published many of the images in the book, “A Child is Born.”

Today, there seems to be a bit of a mystery about where Nilsson may have obtained his images. In fact, Time.com claims that some of those babies he photographed had been aborted:

In the accompanying story, LIFE explained that all but one of the fetuses pictured were photographed outside the womb and had been removed—or aborted—“for a variety of medical reasons.” Nilsson had struck a deal with a hospital in Stockholm, whose doctors called him whenever a fetus was available to photograph. There, in a dedicated room with lights and lenses specially designed for the project, Nilsson arranged the fetuses so they appeared to be floating as if in the womb.

The website Making Visible Embryos, created in part by an historian of biological and medical sciences, makes a similar claim:

Although claiming to show the living fetus, Nilsson actually photographed abortus material obtained from women who terminated their pregnancies under the liberal Swedish law. Working with dead embryos allowed Nilsson to experiment with lighting, background and positions, such as placing the thumb into the fetus’ mouth. But the origin of the pictures was rarely mentioned, even by ‘pro-life’ activists, who in the 1970s appropriated these icons.

Whether allegations that some of the photographed babies came from abortions is true or not is difficult to verify; however, a paper published in Bulletin of The History of Medicine, written by Solveig Julich, associate professor and senior lecturer at the Department of History of Science and Ideas at Uppsala University in Sweden, makes a compelling case. She writes in part:

He admitted that most of the pictures were of “fetuses, just removed surgically” in connection with miscarriages or extrauterine pregnancies. They looked as if they were alive because they were still alive. He had only a few minutes in which to take the pictures before they developed ugly blotches and were changed. A few of the pictures, Nilsson told the reporter, were “taken inside the mother by means of a cystoscope and a flash in connection with a necessary abortion.” But he insisted that his photographs should not be seen as a contribution to the abortion debate: all he wanted to do was to give a clear conception of the origin and development of human life.

In all fairness to Nilsson, now deceased, there is no way to absolutely confirm these allegations nor to understand fully what his motivation was, if, in fact, he did use aborted babies in his photography.

Read the full paper here.

READ: New medical breakthrough could make demand for fetal tissue research obsolete

History is full of examples in which scientists and doctors went too far in their research on human subjects. The most vivid example of this comes out of the Holocaust, during which Nazi physicians believed the medical advances from experiments somehow justified their actions. In an article published by the Montreal Gazette, Dr. Hans Munch, an SS research pathologist at a Nazi institute near Auschwitz, described concentration camp physician Josef Mengele, who experimented on Jews inside the horrific camps:

Mengele saw the gassings as the only rational solution and argued that as the prisoners were going to be gassed anyway, there was no reason not to use them for medical experiments.

Sadly, that kind of reasoning for experimenting on human subjects sounds too familiar, as readers will see in parts two and three of this series on the history of experimentation on abortion survivors.

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Nancy Flanders

·

Investigative

Nancy Flanders

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Abortion Pill

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Human Rights

Carole Novielli

·

Abortion Pill

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·