(Truth from the Heart) I was adopted. More precisely, I’m the poster-child for the fetus who, by all odds, should have been aborted by any standard of modern justification. My biological mother was extremely young — barely a teenager.

Single. The stress of high school. The disappointment of her parents. Goals for the next few years seemed to vanish. Judgment. Financial stress.

It would have been so easy for her to end my life. Everything would have gone back to normal. Nobody would even have to know.

But she didn’t. She didn’t end my life. The reason I can sit here in this chair and breathe and sip my cup of tea and close my eyes and feel gratitude to the core of my being is because a scared little girl allowed me to live and grow inside of her.

Light. Color. Sound. First breath. Inhale. Exhale. Scream.

Life.

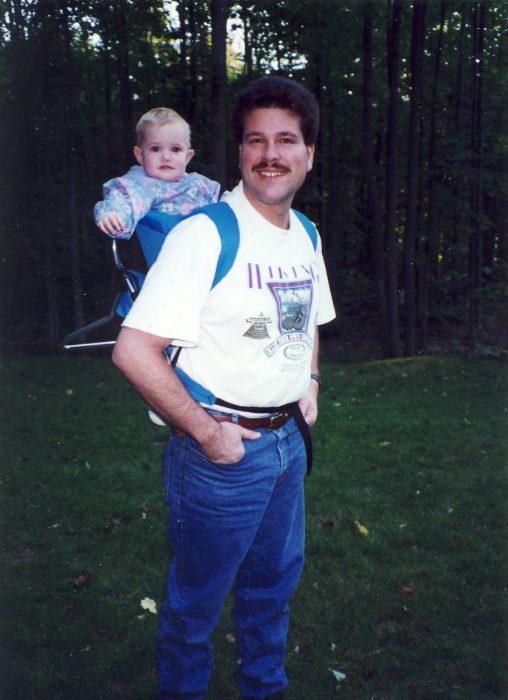

I was brought into the world at a tiny 5 pounds and 10 ounces. The phone rang in my soon-to-be parents’ house. They got the news. Healthy. Alive. Blue-eyed baby girl. She’s breathing and eating and seeing and hearing and feeling. She’s alive.

“Your daughter was born today.”

In that moment, a woman who lived hours away — a woman who (by all odds) never should have met me — became my mother. She would soon become my best friend. My safe place. My shelter. My home. My family.

Fighting back tears, she looked out the window into what would become my backyard — a stomping ground which is now full of memories from the sweetest days of my golden childhood.

Pink roses were in bloom that day.

This was the kind of moment that is so unspeakably beautiful that all you can do is be brave enough to feel it. There is no “orientation” in the school of life. There is no training course on how to handle moments like these; moments which take hold of your entire heart and change the course of your whole existence. We just reverently stand before it in awe.

The little details stick with us. The smells. How the sunlight felt on your skin that day. The song that was playing on the radio. The richness of human experience unfolds before us in these moments.

The simple truth is that the circumstances of my birth have instilled in me a gratefulness and a zeal for life. There’s a whole world out there that I so easily could have missed out on entirely — and I just want to touch all of it.

All of that being said, you would probably find it shocking that I’ve actually been rubbed the wrong way by much of the conversation fostered by Pro-Life movements. While I realize that it’s tricky to generalize an entire movement that consists of many different factions spanning radically different walks of life (for instance, the differences between Catholic Pro-Lifers and secular Feminist Pro-Life groups), I am simply going to speak to my experience with the Pro-Life movement and the observations that I have reflected on for the past several years.

I fear that too much of the Pro-Life debate has revolved around the discussion of rights. I mean, think about it — if you’ve ever gone to the March for Life, can you even begin to count the number of signs that convey something along the lines of: “everyone has a right to life”? This kind of mentality (though correct in its philosophy) is quickly rebutted by: what about the right of the woman to choose?

Since when is the subject of life reduced to a discussion on the evil reality of abortion?

The question is so much bigger than we’ve been thinking. It’s not really a question of whether or not abortion should be legal. That’s not what’s it’s really about.

I would like to propose that the real issue is much, much deeper than that. It’s not about abortion. It’s never been “about” that. It has never been about death.

It’s “about” life in all of its beautiful complexity, and the many complicated questions that people have surrounding what it is to be alive.

What is the meaning of my life? What is my purpose?

Why am I here?

How did I get here?

What is the point?

I think the nature and end of life in itself is the heart of the issue. We as a culture have lost sight of what life is. If we truly grasped and understood the nature and beauty of it, the answer to the problem of abortion would be self-evident. It would automatically be seen as the atrocity that it is.

But people do not understand life.

And so, people do not see abortion for what it is.

And I really think it’s as simple (and grave) as that.

Maybe it’s just that my adoption causes me to see the Movement differently — but I am just so dang grateful for my life, and I think it’s a tragedy that we as a Pro-Life community speak so little about how beautiful life is. We just talk about how ugly abortion is. And that’s true. It is ugly. But I think it’s time to shift the conversation back to life itself — why it truly is so cherished and sacred andworth celebrating.

Yes, we should pray to end abortion. Yes, the March for Life is a wonderful event. Yes, I think lawmakers need to take stands against abortion. But do not mistake abortion as being the locus of the discussion. It’s about life, and the tragedy it is that so many are denied the experience of it.

In a book dedicated to the topic of beauty, Dietrich von Hildebrand could not stop himself from talking about life as a bearer of beauty in general (1). Life is wonderful because “many situations and events in our life are new bearers of beauty…these include especially great, profound experiences, above all love” (2). The beauty of life is the “beauty of the joy that is granted to us” (3).

Life is worth giving to other people because love is worth living for. Love is worthy of being experienced, and being participated in by persons.

Look out of your window a little longer today. Hold your loved ones a little tighter. Be gentle to yourself. Get those flowers you were admiring at the grocery store. You’re alive today. And that’s what it means to be pro-life.

And I just think that something so beautiful is worth talking about.

Let’s make life about… life again.

Editor’s note: Hannah Bruckner is a senior theology student (with a philosophy minor) from Toledo, Ohio. This article originally appeared at Truth from the Heart, and is reprinted here with permission.