In 2006, husband and wife Justin Gadberry and Jalesia McQueen decided to start trying to have children. Through in vitro fertilization, four embryos were created by April 2007 and by November, McQueen had given birth to twin boys. But the other two embryos remained frozen. Six years later, the couple divorced — and disagreed about what should happen to the frozen embryos. Gadberry did not want McQueen to give birth to his two remaining preborn children, while McQueen believed that they were human beings. The disagreement went to trial, and a judge ruled in favor of Gadberry, declaring that the embryos are “property” that could be destroyed.

Gadberry claimed that if McQueen gave birth to the two children, it would violate his constitutional rights by forcing him to have children that he does not want. His lawyer, Tim Schlesinger, celebrated the ruling. “I think today’s ruling is a victory for individuals against unjustified government intrusion,” he said. “We don’t want the government telling when to have children or whether to have children.”

McQueen, however, plans to appeal the decision. “It’s my offspring,” she said. “It’s part of me, and what right do the judges or the government have to tell me I cannot have them?” She’s already named the embryos, too: Noah and Genesis. Gadberry offered several solutions to McQueen — donate the embryos to an infertile couple, donate them to science, keep them frozen, or destroy them — but was unwilling to let her carry them to term, which was the only acceptable solution for McQueen.

“Here’s somebody, my ex, who walks away with no responsibility for having entered into this process voluntarily, of his own free will, with the intention of creating children,” she said. “And that doesn’t account for anything, because his rights supersede mine now, all of a sudden.” Gadberry’s attorney, though, believes that this ruling not only benefits his client, but could also impact other couples in the same situation across the country. “My client’s ex-wife has the right to have children,” Schlesinger said. “But she doesn’t have the right to have children with my client without his consent.”

There’s only one problem with that argument, though: Gadberry already did consent to having children with McQueen. He consented when he supplied his sperm to fertilize her eggs. Those embryos are already human beings, whether he wants to admit it or not. The science behind that is clear, so what he’s really arguing for is, in effect, the right to destroy two of his children because he finds them inconvenient or because he wants to use them as pawns in his divorce.

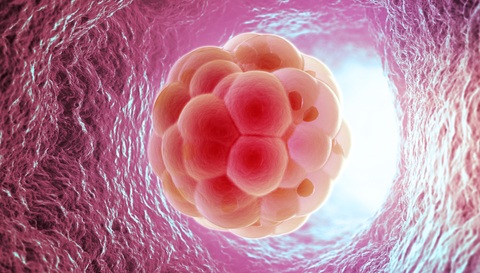

The embryos contain half of Gadberry’s DNA. Yes, they need the right environment to survive — they need to be implanted into a womb. But if Gadberry decided he didn’t want to be a father to their born twins anymore, and deprived them of the things they needed to continue to grow, like food, water, and shelter, it would be a decision that no one would sanction. Just because these other two children are not born yet does not make them any less human.

It’s also important to point out that frozen embryos are not property. They are human beings. And this is one of the fundamental problems with IVF: it turns children into commodities, to be discarded if they are “defective” or unwanted. Instead of being treated as human beings, the preborn babies are too often seen as products to be engineered to the parents’ specifications. Parents will frequently implant themselves with multiple embryos, and then undergo “selective reduction” when they find out they are pregnant with one too many. Babies with Down syndrome are often aborted after IVF. It’s impossible to deny that IVF frequently encourages a troubling mindset that denies preborn children the humanity that they inherently possess.

In this particular case, Gadberry may genuinely not want more children, but his two preborn children should not be treated as property to squabble over in a divorce.

He cannot escape the reality that he is not the father of two children; he is the father of four.