A growing number of Americans call themselves ‘pro-choice’ – but what’s really behind it?

Nancy Flanders

·

The Life at Conception Act: An idea whose time has come

We tend to talk about “ending abortion” as an abstract, faraway goal. Yes, the pro-life movement has the basic outline of a long-term plan to make it happen: either pass a national abortion ban of some kind after changing the makeup of the Supreme Court and getting them to overturn Roe v. Wade, or persuade enough hearts and minds to trump Roe and fully protect the preborn with a Human Life Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Yet the here-and-now conversation is largely preoccupied with marginally reducing abortions by legislating at its peripheries—cutting its practitioners off from the public trough, loading the procedure with ultrasounds and waiting periods, and if we’re lucky, maybe banning 1 percent (15,000, based on “voluntary state reporting and abortion provider survey data from the Guttmacher Institute”) of prenatal killings.

It’s understandable why; when the Supreme Court outright says democracy doesn’t count on a subject, there’s only so much that can be done without incurring their wrath. But I submit that, with the abortion industry’s barbarism laid bare more sharply than ever and scores of pro-lifers finding their patience with letting it continue nearing its breaking point, the conventional wisdom is unsustainable.

We can hope for Roe to be overturned in the next four to eight years, but we can’t credibly predict it—there’s no guarantee the next president with an opportunity to fill SCOTUS vacancies will be pro-life, that his judges will turn out reliable even if he is, that he’ll have a cooperative Senate confirming them, or even which side of the Court will open up first—Antonin Scalia is 79 years old, the same age as Anthony Kennedy, two years older than Stephen Breyer, and only three years younger than Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Clarence Thomas is 67, a good deal younger than most of the pro-abortion Justices…but still far from a guarantee.

A Human Life Amendment faces problems from the other end. It’s a monumental task to first get either a congressional supermajority or two-thirds of the states to propose an amendment and then persuade three-fourths of the states to ratify it, so much so that it’s almost academic—odds are that the kind of electorate you’d need to enact one in the first place would only come about after the country has been turned so overwhelmingly against abortion that they’ve already voted for enough presidents and senators to overturn Roe anyway, and already banned abortion in most states or congressionally. Practically speaking, the HLA wouldn’t be a game-changer for the abortion debate; it would be an epilogue.

Fortunately, there’s another option that seems to have gone relatively unnoticed in many circles. I’ve mentioned it from time to time in previous articles, but now would like to direct your attention to a fuller consideration of the Life at Conception Act. [Disclaimer: the LCA is the top legislative priority of my former employers, the National Pro-Life Alliance.]

Article continues below

Dear Reader,

In 2026, Live Action is heading straight where the battle is fiercest: college campuses.

We have a bold initiative to establish 100 Live Action campus chapters within the next year, and your partnership will make it a success!

Your support today will help train and equip young leaders, bring Live Action’s educational content into academic environments, host on-campus events and debates, and empower students to challenge the pro-abortion status quo with truth and compassion.

Invest in pro-life grassroots outreach and cultural formation with your DOUBLED year-end gift!

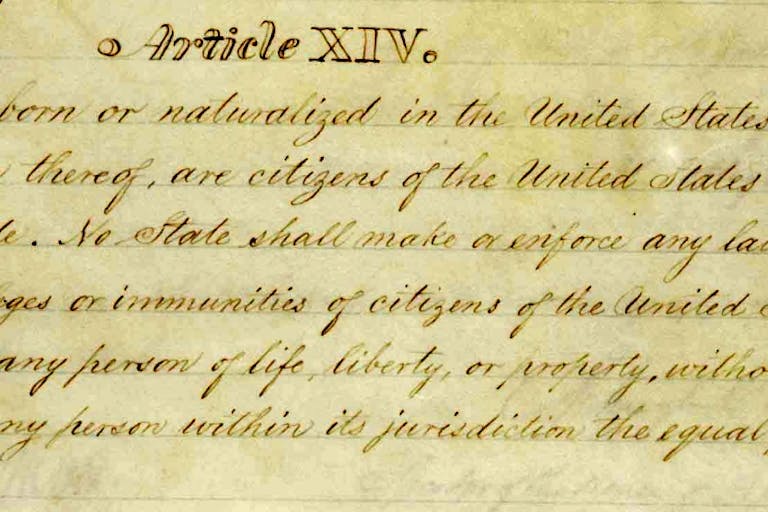

Roe v. Wade gets many, many things scandalously wrong, but it concedes the most important legal point of all:

The appellee and certain amici argue that the fetus is a “person” within the language and meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. In support of this, they outline at length and in detail the well known facts of fetal development. If this suggestion of personhood is established, the appellant’s case, of course, collapses, for the fetus’ right to life would then be guaranteed specifically by the Amendment. The appellant conceded as much on reargument.

Of course, they got around that by pretending personhood couldn’t be established (never mind that the Fourteenth Amendment’s primary drafter, John Bingham, expressly stated it was mean to apply to “any human being,” or that the top legal minds informing the Constitution’s authors taught that the right to life begins well before birth). But legally, easily disprovable obstinacy over empirical scientific facts matters far less than the fact that in the above passage, Roe opened the door to its own destruction.

The Life at Conception Act seizes upon this passage and essentially calls Roe’s bluff by declaring that “each and every member of the species homo sapiens at all stages of life, including the moment of fertilization” qualifies as a human being owed equal protection of his or her constitutional right to life. The LCA’s advantages over both the HLA or waiting for overturn are tremendous.

It would only need a congressional majority and a president’s signature. As a bill to restore democracy on abortion rather than directly criminalize it (though it would effectively ban abortion in the fifteen states with pre-Roe abortion bans still on the books or laws meant to take effect once Roe falls), it sidesteps questions like rape exceptions, enabling proponents to focus on their most unifying arguments (whereas pro-lifers who tolerate exceptions in incremental bills would rightly deem the prospect of enshrining them in a constitutional amendment far les palatable, making HLA messaging far more complicated).

And while it’s admittedly no guarantee that SCOTUS wouldn’t conjure up a new pretext for striking the LCA down, the shrewd use of Roe’s own words, casting the bill almost as an application of the ruling rather than a rejection of it, just might be the sort of unorthodox move that speaks to Justice Anthony Kennedy’s conflicted sensibilities on the subject. Besides, judicial disenfranchisement of pro-life voters has been an intractable obstacle to saving lives for so long that surely any chance of ending it once and for all is worth taking, and there are plenty of additional measures to stop it we can and must take anyway.

States have made tremendous progress on incremental pro-life laws over the past several years, but ultimately Roe keeps legal abortion secure well into the second trimester. The Human Life Amendment is too far off to help us, and waiting for Supreme Court to undo their own obstructionism is not a viable strategy. However, a proactive campaign to make Roe obsolete via the Life at Conception Act gives the pro-life movement a serious chance at a real political breakthrough.

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Nancy Flanders

·

Analysis

Cassy Cooke

·

Analysis

Cassy Cooke

·

Analysis

Cassy Cooke

·

Analysis

Cassy Cooke

·

Analysis

Nancy Flanders

·

Guest Column

Calvin Freiburger

·

Abortion Pill Reversal

Calvin Freiburger

·

Guest Column

Calvin Freiburger

·

Abortion Pill Reversal

Calvin Freiburger

·

Activism

Calvin Freiburger

·