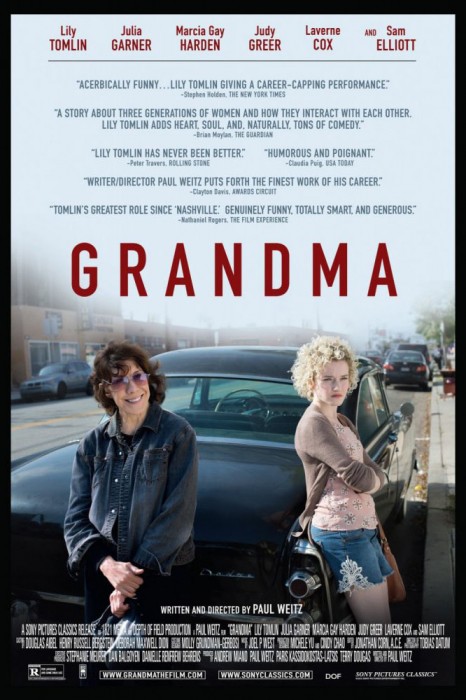

Back in February, we told you about Grandma, a “family comedy” about abortion, more specifically a woman trying to help her granddaughter raise money for one. And much like “Obvious Child” before it, critics are celebrating its release with odes to its biases, pretending its shallow and one-sided presentation of the subject is actually courageous sophistication, based on nothing more than the fact that it tells them what they want to hear.

Back in February, we told you about Grandma, a “family comedy” about abortion, more specifically a woman trying to help her granddaughter raise money for one. And much like “Obvious Child” before it, critics are celebrating its release with odes to its biases, pretending its shallow and one-sided presentation of the subject is actually courageous sophistication, based on nothing more than the fact that it tells them what they want to hear.

In the New York Times, AO Scott calls it a “sweet, smart” film, with Lily Tomlin’s titular grandmother Elle defined in large part by “her uncompromising commitment to behaving like a free human being.” He lavishes praise on the film for the “sympathy” with which it regards Elle, daughter Judy, and granddaughter Sage… while conspicuously ignoring the total lack of sympathy for the great-granddaughter our protagonists seek to destroy.

Scott also references the “distinct risks and opportunities each one faces as she tries to pursue happiness and avoid compromise”—an inadvertent confession that uncompromised happiness is the highest good of the pro-abortion mind, the harm we inflict in pursuit of it be damned.

Next, Vulture’s David Edelstein’s review doesn’t focus much on abortion, but finds time to sneer that the “light” and “matter-of-fact treatment” of the subject and others supposedly reflects their essence in the real world, “the world that exists beyond the Duggars, the Republican primary, and in pockets of the country where four-times-married county officials refuse to marry gays because their lifestyle runs counter to the Christian Bible.” You might want to take a gander at the world that exists beyond your own social circles, David.

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone cheers Tomlin’s character for “tak[ing] on the world like the hypocrisy pit it is,” apparently oblivious to the hypocrisy of demanding a child needlessly die in the name of your own humanity and self-determination.

Meanwhile, Slate’s June Thomas hails the film’s handling of abortion as “revolutionary,” claiming it treats the subject “with utmost seriousness” and noting that “the responsibility is spread around—Sage for making reckless decisions; Judy for paying more attention to work than to her daughter; and Elle’s generation for failing to make abortion widely available at a reasonable price.”

Funny how her definition of “responsibility” amounts to nothing more than lip service to Sage’s “reckless decisions,” yet it doesn’t extend to taking responsibility for the new human life she’s created. That’s the exact opposite of responsibility and it’s scandalously unserious. And how is it revolutionary to indulge in the same old narcissistic “abortion is all about my body!” delusion pro-aborts have been peddling forever?

But even more surreal is Thomas’s declaration that Elle is “also someone’s grandma—and at the end of the movie, she seems ready to recommit to that role.” By, er, shirking the reality that she was also a great-grandmother.

Alonso Duralde at the Wrap calls it “smart and sweet, mature and bawdy, knowing its characters’ flaws yet open to the possibilities of people acting upon their best instincts.” The granddaughter in the move is reportedly ten weeks pregnant. At that stage, a recognizably-human baby is killed, extracted, and sometimes removed one limb at a time. His or her gory death looks anything but “sweet.”

Does it seem “mature” to you to sweep such violence under the rug just because it gets the desired result? Is murdering someone so defenseless, fully dependent on you for their basic welfare due to your own conscious actions, really an embodiment of one’s “best instincts”?

But the most extensive discussion of the film’s abortion aspect comes from Shannon Kelley at Talking Points Memo, who gushes that it’s “so real and so nuanced and so normalizing”:

[T]he abortion is handled with a kind of understated complexity that’s still exceedingly rare on film. There are no grand speeches, nor is there any question that it should be an option, safe and available, or that it is likely the best choice for Sage, who is still in high school, wants to go to college, and has a terrible boyfriend.

Kelley actually typed that the movie contained “complexity” in one sentence and that it never questioned abortion’s legitimacy in the very next. And didn’t notice the contradiction. Nor did her editors. And pro-lifers are the ones blinded by religious-like zeal?

We learn this in a searing scene at a visit of last resort to see Karl (a de-whiskered, un-cowboy-hatted Sam Elliott), a long-ago ex of Elle’s. The reunion is filled with tension and steam and is loaded with unfinished business and not-entirely-healed wounds. He’s still furious; she insists it was her body, her life. Elle needed to untie herself from their relationship so she could finally accept herself and live according to who she really was—but she hurt a man she loved, and who loved her.

The tiny matter of her also hurting their son or daughter is naturally ignored. Complexity!

It’s bold enough to say that abortion can be hard and painful and maybe even one of those choices a woman questions years down the road—and that it can still be the right choice, and that it absolutely should be available, to every woman, as a choice.

While ignoring the central reason that pain occurs. While not explaining why it can be a right choice, or having the courage to confront the reasons it might not be.

Grandma is about grief, about idealism, about aging, about intergenerational relationships between women. That something can be both right and painful, that there are no easy choices, that the past is never past, that we will let ourselves and our loved ones down, that our loved ones will let us down.

And that sometimes we’ll kill those loved ones because society told us it was our “right,” the entertainment industry will make movies idolizing us for doing so, and pretentious critics will write odes to the “sweetness” and “idealism” of killing them.

These reviews are, of course, repellant, but it’s ultimately not too surprising to see what debauchery some film critics are untroubled by. Far more alarming is how voices of decency in the field are almost universally absent. Rotten Tomatoes has compiled 46 reviews for Grandma, only four of which are negative. Metacritic has 19 favorable reviews, four mixed ones, and zero that are outright negative.

But the kicker? None of the eight outliers cite the film’s abortion promotion as one of their reservations. It’s another reminder that, even though the majority of the country is on our side and many more are sympathetic, in many ways uprooting this cultural desensitization to prenatal violence will still be an uphill battle.