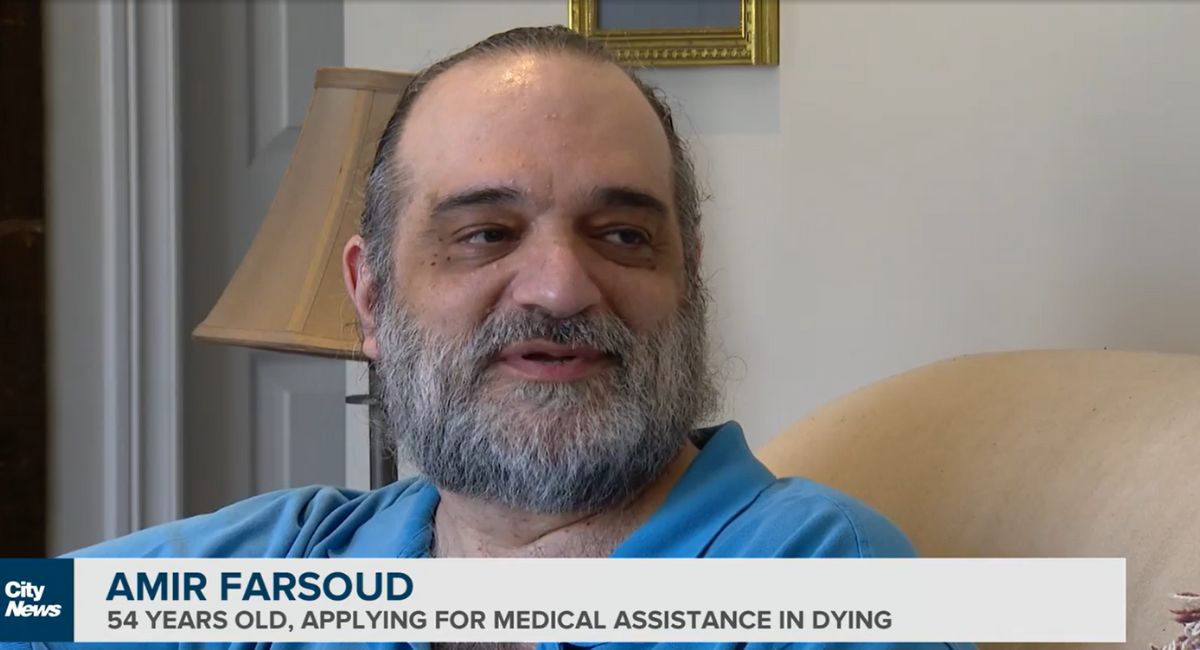

A 54-year-old man in Ontario, Canada, has applied for Medical Aid in Dying (MAiD) — not because he’s ill, but because he’s facing the loss of his house and fears becoming homeless.

Amir Farsoud told City News Everywhere that he has struggled with a back injury that has left him with constant pain. At times, he said he is “crying like a 5-year-old and not sleeping for days in a row,” and that his life is “awful, non-existent and terrible … I do nothing other than manage pain.”

Yet despite this, he still wanted to continue living — until the home he shares with two roommates was put up for sale. As he receives social assistance, he can’t find another place to live within his budget and fears becoming homeless. So he has applied for MAiD.

“I don’t want to die but I don’t want to be homeless more than I don’t want to die,” he said. “I know, in my present health condition, I wouldn’t survive it [homelessness] anyway. It wouldn’t be at all dignified waiting, so if that becomes my two options, it’s pretty much a no-brainer.”

Farsoud added that if he wasn’t facing homelessness, he wouldn’t be considering MAiD.

“It would be on my radar because my physical condition is only going to get worse,” he said. “At that point, I would be probably availing myself of the option, but that would be presumably years down the road.”

Dr. Kerry Bowman, a bioethicist from the University of Toronto, told City News Everywhere that Canada’s lax euthanasia laws have led to more and more people with disabilities, like Farsoud, seeking MAiD. “Cases like [Farsoud’s] are emerging with increasing frequency across the country. We were unbelievably naive as a nation to think that vulnerability, disability, poverty that we could parcel that off and it wasn’t going to be a problem. It’s a huge problem,” Bowman said.

“I worry about this because it is people living with disability, people living with pain, people living in poverty, that are requesting medical assistance in dying, not because of the physical experience they’re going through, but because of the social circumstances themselves and this is wrong. It’s really a very terrible thing.”

The United Nations’ first Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Catalina Devandas Aguilar, toured Canada in 2019 and, even then, said people with disabilities were being overlooked, deprived of needed health care, and pushed into assisted suicide. “I am extremely concerned about the implementation of the legislation on medical assistance in dying from a disability perspective,” she wrote. “I have been informed that there is no protocol in place to demonstrate that persons with disabilities have been provided with viable alternatives when eligible for assistive dying. I have further received worrisome claims about persons with disabilities in institutions being pressured to seek medical assistance in dying, and practitioners not formally reporting cases involving persons with disabilities.”

Since then, the situation has only gotten worse, as Canadians increasingly seek MAiD due to disability and poverty.

For his part, Farsoud made it clear that he doesn’t actually want to die.

“I think it’s horrible, whether it’s ethical or not, but I think it’s backwards. I think in a country such as ours, people shouldn’t be hungry and shouldn’t be worried about whether there’s a roof over their head,” he said. “I think we actually have the wherewithal for that not to be an issue and that we are choosing to not help the most vulnerable members of the society is tragic.”