Women and men discuss abortion coercion and regret 'Face to Face'

Cassy Cooke

·We are urgently seeking 500 new Life Defenders (monthly supporters) before the end of October to help save babies from abortion 365 days a year. Your first gift as a Life Defender today will be DOUBLED. Click here to make your monthly commitment.

Investigative·By Carole Novielli

Past Planned Parenthood president instrumental in pushing to decriminalize abortion

This article is part of a series on the history of Planned Parenthood. Read parts one, two, and four.

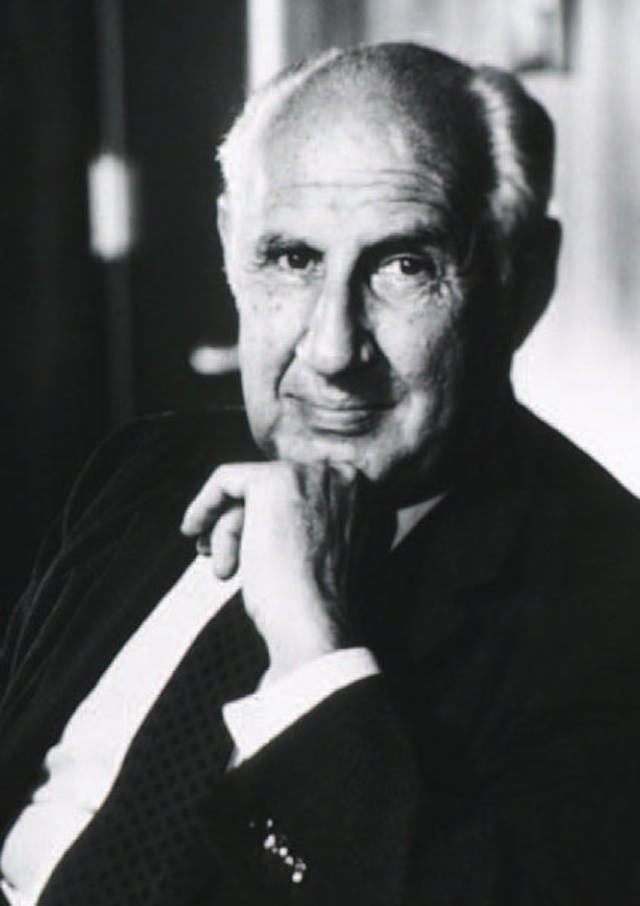

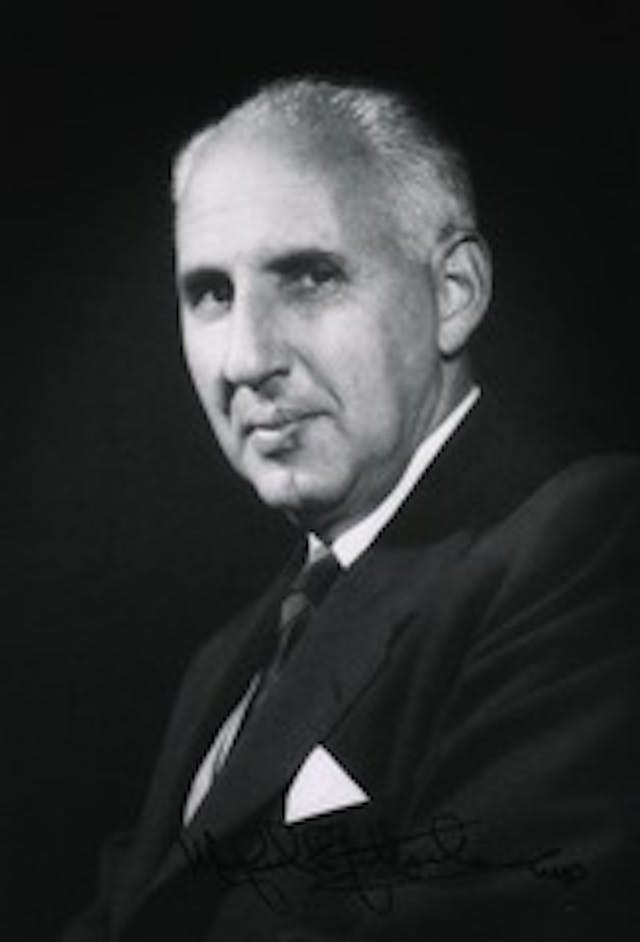

In reviewing the genesis of Planned Parenthood’s obsession with abortion, their founder Margaret Sanger’s views on forced sterilization and birth control, we’ve learned that it was actually under Alan F. Guttmacher’s presidency that abortion became part of Planned Parenthood’s mission. In the second part of this series, we gave some context to just how long Guttmacher had been pushing abortion prior to becoming a leader of Planned Parenthood. In part three, we will detail when Planned Parenthood publicly began to call for the legalization of abortion and began referring for the procedure.

In 1962, Guttmacher became president of Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA) and shortly thereafter, he told a friend, “I have not had the fortitude” to present to PPFA the idea of promoting abortion. “I think I would have a tough time in getting them to take a stand” he said. Any open support for legal change, he said, according to author David J. Garrow, “is going to take a long time.”

In reality, it did not take long at all.

Pushing the “health exceptions” and redefining “life of the mother”

Guttmacher had been an outspoken advocate of decriminalizing abortion for years, but he became especially obsessed with abortion while in New York, eventually serving (in 1968) on Governor Rockefeller’s commission to examine the abortion statute in the state and make recommendations for change. In comparing the abortion rate of New York hospitals, Guttmacher observed that more whites than minorities were having abortions, writing, “the ratio of therapeutic abortions per 1000 live births was 2.6 for whites, 0.5 for Negroes, and 0.1 for Puerto Ricans…. [D]iscrimination between ward and private patients and between ethnic groups served to aggravate my dissatisfaction with the status quo and led to my desire for the enactment of a new law.”

Guttmacher was a Humanist who did not view the life of the child as equal to the woman. He can be credited with pushing the so-called “health exceptions” for abortion. “By defining ‘life’ to include mental well being… Guttmacher claimed that there were instances in which it was appropriate to protect a woman’s ‘life’ by taking the life of her fetus,” writes abortion historian Daniel K Williams:

“I don’t like killing,” Guttmacher stated in a public lecture in 1961.

“I don’t like to do abortions but as many of you probably fought in World War II and killed because you wanted to preserve something more important, I think a mother’s life is more important than a fetus.”

Guttmacher’s focus on abortion for health purposes might be attributed to his twin brother, Dr. Manfred Guttmacher, a psychiatrist who happened to be a member of the American Law Institute (A.L.I.). The two Guttmacher brothers were both activists in the first birth control clinic in Baltimore.

“I have great respect for the American Law Institute. My twin brother Manfred, also a physician, an authority on forensic psychiatry, is a member of this group. Because of our twinship, I was privileged to attend a closed meeting two years ago,”Guttmacher wrote in Babies by Choice or Chance, in 1961.

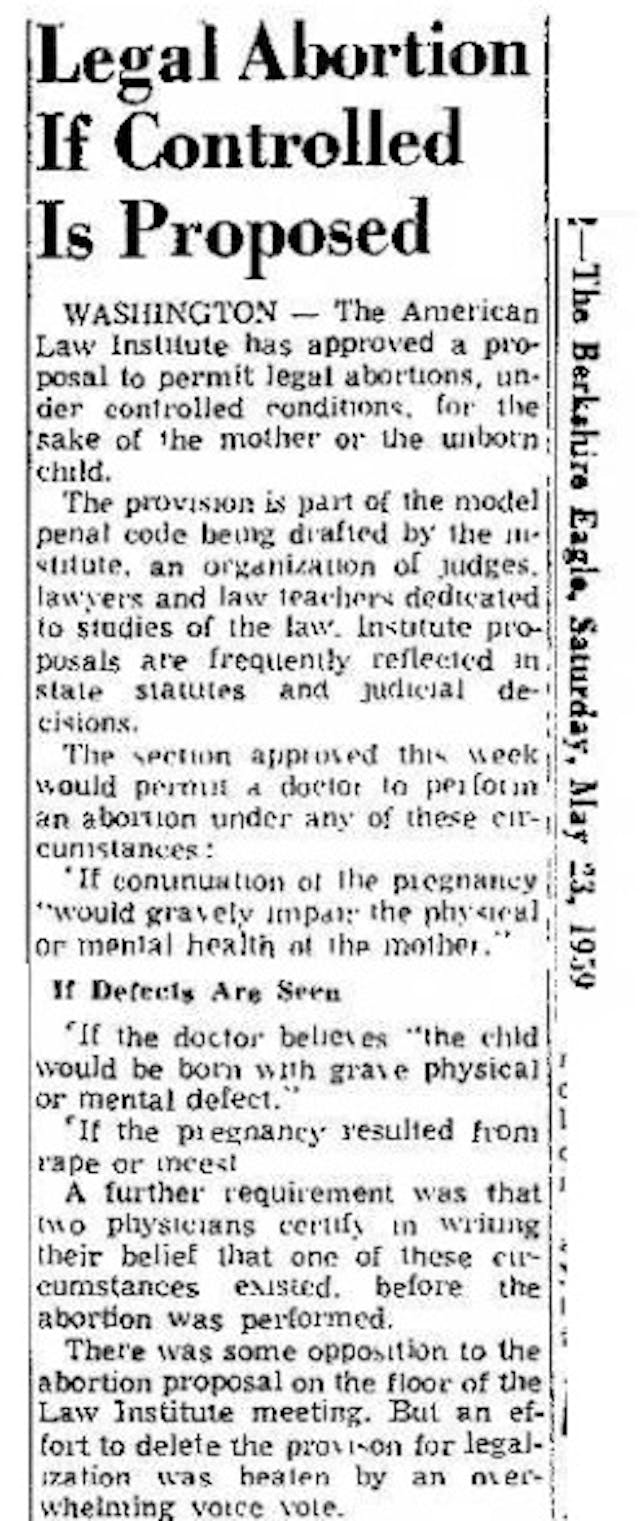

According to the University of Pennsylvania Law School, the ALI was founded in 1923 and was made up of a group of judges, lawyers, and law professors, “to promote the clarification and simplification of the law and its better adaptation to social needs, to secure the better administration of justice and to encourage and carry on scholarly and scientific legal work.” It was the ALI’s Model Penal Code on abortion that was used in the infamous Roe v. Wade Supreme Court ruling that forced abortion on every state in the nation.

Guttmacher later described that closed meeting further in 1972:

[O]n a Sunday afternoon in December, 1959 when Mr. Herbert Wechsler (Professor of Law at Columbia) unveiled his model abortion statute now called the A.L.I. bill. The recommended statute provided that a doctor would be permitted to perform an abortion:

(1) if continuation of pregnancy “would gravely impair the physical or mental health of the mother”;

(2) if the doctor believed “that the child would be born with grave physical or mental defects”; or

(3) if the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest.”

“The Wechsler abortion bill was passed by the Institute as part of the total revised penal code revealed to the public in 1962. Many, including myself, hailed it as the answer to the legal problems surrounding abortion, which had always been the doctors’ dilemma,”Guttmacher recounted, adding, “In 1967, Colorado, California, and North Carolina… and in 1968, Maryland and Georgia… all modified their respective statutes using the A.L.I. bill as the prototype.”

“Even though the A.L.I. Code had not yet been adopted by any state, its mere promulgation opened the medical profession’s eyes to the preservation of health as being a justification for abortion,” Guttmacher wrote.

The real reason for the abortion push: population control and eugenics

Guttmacher’s and Sanger’s views were very similar, as they were both vocal members of the eugenics community. Sanger once advocated that a woman should obtain a license to breed in order to have a child, while Guttmacher pushed the idea that “feeble-minded” and “unfit” persons should have abortions. He was, however, clever enough to say that these were to be voluntary measures, despite a history of force within the population control movement.

As author Donald T. Critchlow explained in his book, “Intended Consequences,” “Within Planned Parenthood… population control advocates found a prominent place. Thus, Planned Parenthood maintained its position of promoting birth control as a woman’s right, but it joined other groups in lobbying for family planning as a means of controlling the rate of population growth.”

In his 1959 book, “Babies by Choice or by Chance,” Guttmacher writes:

It is my belief that it should be permissible to abort any pregnancy in which there is high likelihood of injury to the health of the mother, or one in which there is a strong probability of an abnormal or malformed infant. In addition, the quality of the parents must be taken into account. Feeble-mindedness, in the mother in particularly, and her ability to care for a child should be evaluated. Pregnancy occurring from proved rape, and pregnancy in a child less than sixteen serves no useful purpose. Further, chronic moral turpitude which unfits humans as parents, such as drug addiction or chronic alcoholism, if declared incurable, should furnish ground for pregnancy interruption.

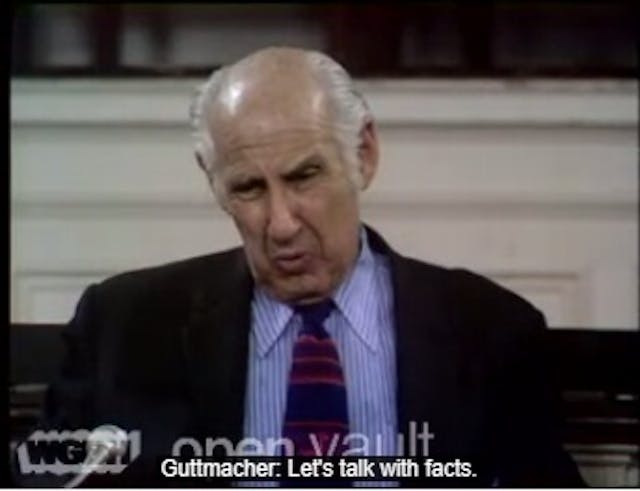

On December 4, 1967, Guttmacher appeared on a panel at Harvard Law School to discuss which types of people Hospitals should approve for abortions. He admitted:

“… I would abort mothers already carrying three or more children…. I would abort women who desire abortion who are drug addicts or severe alcoholics…. I would abort women with sub-normal mentality incapable of providing satisfactory parental care…”(Source; “Abortion: The Issues”, Dr. Alan Guttmacher – President, Planned Parenthood, December 4, 1967, Harvard Law School Forum)

Lying about motives… and about illegal abortion deaths

Abortion was strategically pushed on the nation, as Live Action News has previously reported, through lies and deceptions on the numbers of women who died from illegal abortions. And yet, a 1967 article in the Harvard Crimson quoted Alan Guttmacher speaking at the Harvard Law School Forum, admitting that most abortions prior to legalization were performed by “reputable physicians” – something that was downplayed as advocates pushed legal abortion as being safer than illegal abortion:

Seventy per cent of the illegal abortions in the country are performed by reputable physicians, each thinking himself a knight in white armor.

At the same event, Guttmacher asked for liberalization of abortion laws, but according to a report published by the Harvard Crimson, not for outright repeal. He said, “To allow abortion on demand would relegate man to the status of the bull.”

The next year, in 1968, Guttmacher founded the Center for Family Planning Program Development, a “special affiliate” of Planned Parenthood, later renamed The Alan Guttmacher Institute. The organization, according to their website, was “originally housed within the corporate structure of Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA).” In a speech he made in July of 1969, Guttmacher acknowledged that funding for his Institute came from grants “from the Kellogg, Rockefeller, and Ford Foundations as well as several other lesser foundations.” Some of these same organizations had been funding eugenics for years.

In April 1969, Guttmacher suggested adding a clause to permit abortion in New York for any woman over 40 years of age, but it was voted down. He also believed that “abortion statutes should be entirely removed from the criminal code.”

Dear Reader,

Every day in America, more than 2,800 preborn babies lose their lives to abortion.

That number should break our hearts and move us to action.

Ending this tragedy requires daily commitment from people like you who refuse to stay silent.

Millions read Live Action News each month — imagine the impact if each of us took a stand for life 365 days a year.

Right now, we’re urgently seeking 500 new Life Defenders (monthly donors) to join us before the end of October. And thanks to a generous $250,000 matching grant, your first monthly gift will be DOUBLED to help save lives and build a culture that protects the preborn.

Will you become one of the 500 today? Click here now to become a Live Action Life Defender and have your first gift doubled.

Together, we can end abortion and create a future where every child is cherished and every mother is supported.

“Family planning” not welcomed by minorities

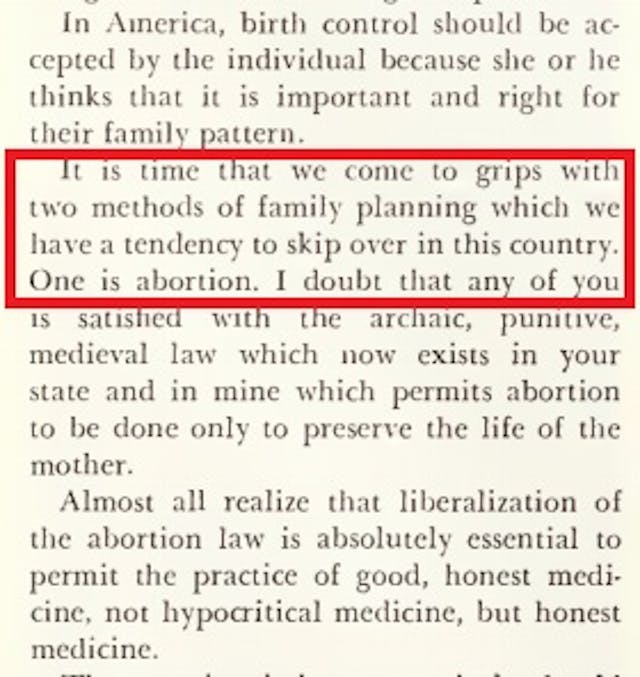

Guttmacher called abortion “family planning,” and, in that same July 1969 speech, he pushed the decriminalization of abortion, saying, “It is time that we come to grips with two methods of family planning which we have a tendency to skip over in this country. One is abortion. I doubt that any of you is satisfied with the archaic, punitive, medieval law which now exists in your state and in mine which permits abortion to be done only to preserve the life of the mother. Almost all realize that liberalization of the abortion law is absolutely essential to permit the practice of good, honest medicine, not hypocritical medicine, but honest medicine. The question is how extensively should we liberalize the law.”

The problem they had was that the very people which Sanger and her eugenics boards (and Guttmacher with his abortion advocacy push) targeted, the Black community, viewed birth control and abortion to be genocidal efforts to limit the growth of the Black race. And Planned Parenthood had noticed that their own minority patients had been on the decline. “Figures for ethnicity only go back to 1964 when 47% of the total patients were nonwhite. This dropped to 39% five years later in 1968,” Guttmacher stated.

Guttmacher acknowledged this in his speech:

“In addition, we must take full cognizance of the fact that our work among some militant minority groups is considered genocidal. They charge that what we are doing is not really trying to give a better family life to the less privileged segments of the community but trying to retard the numerical growth of ethnic minorities. This was first brought to my attention five or six years ago when I was lecturing at the University of California. For the first time in a long life I was picketed, and this fascinated me. I was picketed by a group called EROS, so I went down and chatted with the pickets who were very intelligent-looking black men. EROS means Endeavor to Raise Our Size…. They protested the work of PPWP as a form of genocide.”

Black suspicions ran even higher, when during a 1969 White House conference on food, nutrition and health, Guttmacher again unashamedly pushed for the decriminalization of abortion.

His statements, along with comments by others at the conference, were supposed to be aimed at helping the poor with food, but, instead, he was pushing population control. This alarmed Black activists like Fannie Lou Hamer, who, the night before the conference ended, issued a scathing attack on Guttmacher and others of like mind, according to a report filed on December 20, 1969, by the The Free Lance-Star. The paper quoted the noted civil rights activist as denouncing voluntary abortion, calling it “legalized murder,” making it clear that “she regards it as a part of a comprehensive white man’s plot to exterminate the Black population of the United States.”

The paper then went on to defend Guttmacher’s eugenic motives as “humanitarian.”

A January 28, 1966, internal memo from Alan Guttmacher and Fred Jaffe acknowledged that Planned Parenthood was aware of how the Black community viewed abortion. The memo outlined the plan for winning over the Black community, calling for a “Community Relations Program” to “form a liaison between Planned Parenthood and minority organizations.” The plan, according to Planned Parenthood, would emphasize that “all people have the opportunity to make their own choices,” rather than, as the memo states, “exhortation telling them how many children they should have.”

One way to get the message out, according to the memo, is to “get assistance from black organizations like The Urban League and the AME church,” and to employ “more Negro staff members on PP-WP [Planned Parenthood-World Population] and Affiliate’s staff, as well as recruit more Negro members for the National Board – at least 5.”

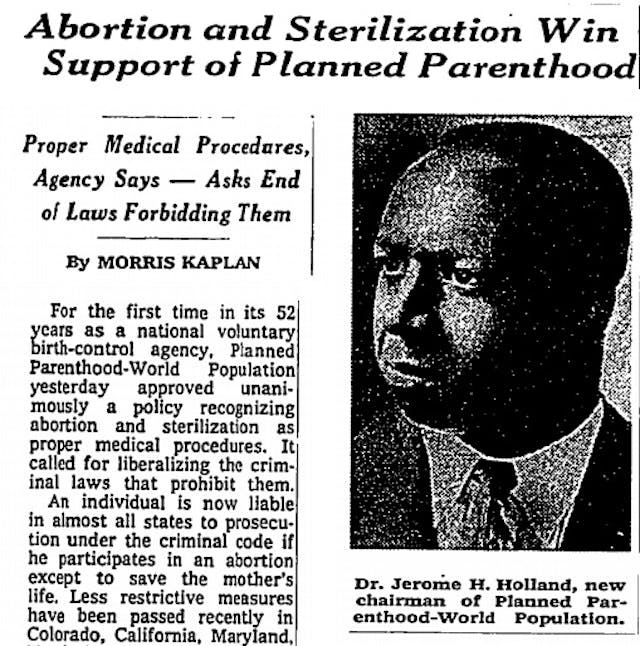

Planned Parenthood approves abortion advocacy

A few short years later, in 1968, Planned Parenthood did just that. Coincidentally, the move to add more Black board members came at the same time that the organization unanimously approved a policy recognizing abortion and sterilization as proper medical procedures.

According to the New York Times, “It called for liberalizing the criminal laws that prohibit them.”

At that same meeting, Planned Parenthood elected the first Black board chairman as the face to push this new abortion agenda — Dr. Jerome H. Holland, who, according to the NYT, “pledged his support for the group’s program saying that those who call birth control a form of genocide are ‘not aware of the real meaning of family planning and its uses.'”

Guttmacher expressed pleasure that “the group had taken a positive stand on ‘the necessity to liberalize abortion and sterilization statutes,'” adding that abortion should never be used as birth control. The recommendation affirmed by the 100-member board had originated from Planned Parenthood’s medical advisory committee, which Guttmacher had been part of. That committee had held:

“[I]t was the right and responsibility if every woman to decide whether and when to have a child…

“The committee recommended the abolition of existing laws and criminal laws regarding abortion and the recognition that advice, counseling and referral constituted an integral part of medical care…It recommended also that Planned Parenthood centers offer appropriate information and referral,” the NYTs reported.

The board then took Guttmacher’s advice to stress “voluntarism” with regard to legalizing abortion as the best way to reduce population.

“After this plank was approved in 1969,” writes Larry Lader in “Abortion II,” “PP chapters soon started abortion referrals, and even clinics, as ‘an integral part of medical care.'”

Planned Parenthood refers for abortions

In fact, by 1970, Planned Parenthood of New York had announced according to the New York Times, “a citywide abortion information and referral service would be in operation on July 1, when the state’s new abortion law takes effect. The service will advise women on abortions and refer them to doctors and hospitals willing and able to perform the operations.”

That same year, Guttmacher added, “We look forward to the time when our clinics can be closed, when the government can fund enough money to serve the poor and research new birth control methods.”

In our next article in this series, we will discuss Planned Parenthood’s first abortion facility, which did not open until 1970, and will detail Alan Guttmacher’s role in the idea of stand-alone abortion facilities, revealing how abortion came to be seen as the ultimate method of population control.

This was part three in Live Action News’ series on the history of Planned Parenthood’s move to committing abortions. You can read part one, part two, and part four in additional articles.

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Cassy Cooke

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Bridget Sielicki

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Investigative

Bridget Sielicki

·

Investigative

Bridget Sielicki

·

Investigative

Carole Novielli

·

Abortion Pill

Carole Novielli

·

Abortion Pill

Carole Novielli

·

Abortion Pill

Carole Novielli

·

Abortion Pill

Carole Novielli

·