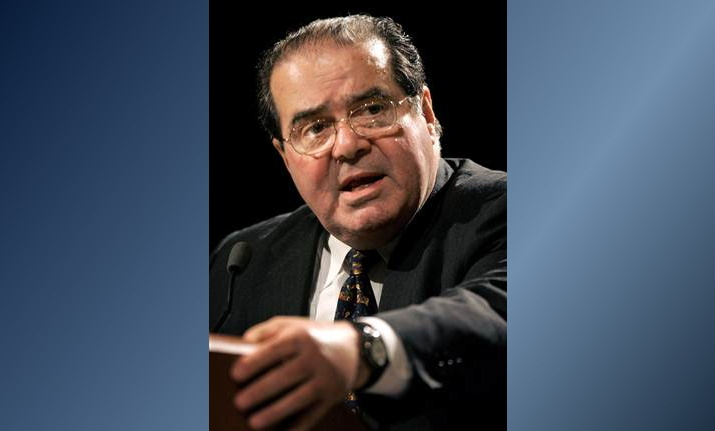

Over the weekend, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia appeared on Fox News Sunday to chat with Chris Wallace about his new book, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts. (Video here, transcript here.) The exchange is invaluable to understanding the judicial aspects of the abortion debate.

Over the weekend, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia appeared on Fox News Sunday to chat with Chris Wallace about his new book, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts. (Video here, transcript here.) The exchange is invaluable to understanding the judicial aspects of the abortion debate.

First, Scalia explains his general approach to constitutional interpretation:

Originalism is sort of subspecies of textualism. Textualism means you are governed by the text. That’s the only thing that is relevant to your decision, not whether the outcome is desirable, not whether legislative history says this or that. But the text of the statute. Originalism says that when you consult the text, you give it the meaning it had when it was adopted, not some later modern meaning.

The left’s preferred alternative is “Living Constitution” theory, which holds that our interpretation of the Constitution must change alongside society’s changing values and desires, because, as President Woodrow Wilson put it, government is “a living thing … modified by its environment, necessitated by its tasks, shaped to its functions by the sheer pressure of life. No living thing can have its organs offset against each other as checks, and live.”

Simply put, this is a sham that defeats the whole point of having a Constitution: placing firm limits on what government can do to the people and what people can do to each other. This function will never change because essential human nature is constant, as is the moral truth at America’s core – the equal right of every human being to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Yes, the Constitution is imperfect, and our preferences may change. But when they do, the only legitimate way to incorporate those changes into the Constitution is through the amendment process, which guarantees that changes happen only for matters of the utmost importance and preserves the integrity of the rest of the document – as opposed to simply reinterpreting it to suit our whims and agendas, which paves the way for rationalizing anything government might want to do to the people.

Later, the conversation turns to one of our history’s starkest examples of what happens when originalism is abandoned in favor of Living Constitutionalism:

WALLACE: There is one Supreme Court decision, reading a lot of your writings and speeches over the years, that seems to distress you more than any other. And that is Roe versus Wade, the 1973 decision that says that women have a constitutional right to abortion. You say that it is it a lie. And, in fact, while generally willing, you say, to accept long standing precedents, you say you will continue to press to overturn Roe. Why?

SCALIA: Well, I’m not sure if I could say this distresses me more than any other. It is in my mind the clearest example of being a non-textualist and non-originalist. No one ever thought that the American people ever voted to prohibit limitations on abortion. I mean, there is nothing in the Constitution that says that.

WALLACE: What about the right to privacy that the court found in known 1965?

SCALIA: There is no right to privacy. No generalized right to privacy.

WALLACE: Well, in the Griswold case, the court said there was.

SCALIA: Indeed it did, and that was — that was wrong. In the earlier case, the court had said the opposite. Look, the way the Fourth Amendment reads that people shall be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures.

To grasp just how badly the court stretched the Constitution’s privacy protections, consider that Griswold v. Connecticut’s author, Justice William Douglas, justified his decision by claiming that “specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance,” meaning he wasn’t looking to the actual text of the Constitution, but instead imagining what he wanted to find in the vague shadow of an emanation – pure gibberish.

Further, a pregnant woman’s right to privacy cannot possibly encompass abortion for the simple fact that it’s not private; it also affects someone other than that woman. The Roe court simply punted on the case’s most important factor, declaring, “We need not resolve the difficult question of when life begins.”

Lastly, it’s worth remembering that Scalia’s not exactly out on a limb here – even many liberal and pro-choice legal scholars admit that Roe is an embarrassment. For instance:

Laurence Tribe — Harvard Law School. Lawyer for Al Gore in 2000.

“One of the most curious things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found.”

“The Supreme Court, 1972 Term—Foreword: Toward a Model of Roles in the Due Process of Life and Law,” 87 Harvard Law Review 1, 7 (1973).

Edward Lazarus — Former clerk to Harry Blackmun.

“What, exactly, is the problem with Roe? The problem, I believe, is that it has little connection to the Constitutional right it purportedly interpreted. A constitutional right to privacy broad enough to include abortion has no meaningful foundation in constitutional text, history, or precedent – at least, it does not if those sources are fairly described and reasonably faithfully followed.”

“The Lingering Problems with Roe v. Wade, and Why the Recent Senate Hearings on Michael McConnell’s Nomination Only Underlined Them,” FindLaw Legal Commentary, Oct. 3, 2002

John Hart Ely — Yale Law School, Harvard Law School, Stanford Law School

Roe “is not constitutional law and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be.”

“The Wages of Crying Wolf: A Comment on Roe v. Wade,” 82 Yale Law Journal, 920, 935-937 (1973).Kermit Roosevelt — University of Pennsylvania Law School

“You will be hard-pressed to find a constitutional law professor, even among those who support the idea of constitutional protection for the right to choose, who will embrace the opinion itself rather than the result. This is not surprising. As constitutional argument, Roe is barely coherent. The court pulled its fundamental right to choose more or less from the constitutional ether.”

“Shaky Basis for a Constitutional ‘Right’,” Washington Post, January 22, 2003.

Shamefully, few pro-abortion activists are willing to right this constitutional wrong and return abortion policy to the democratic process, because all they care about is preserving their preferred result. So let’s ask our pro-choice readers: are you willing to put the Constitution above your ideology? Do you recognize any higher goods to which the “right to choose” must yield?