New Archbishop of Canterbury warns of danger in legalizing assisted suicide

Nancy Flanders

·

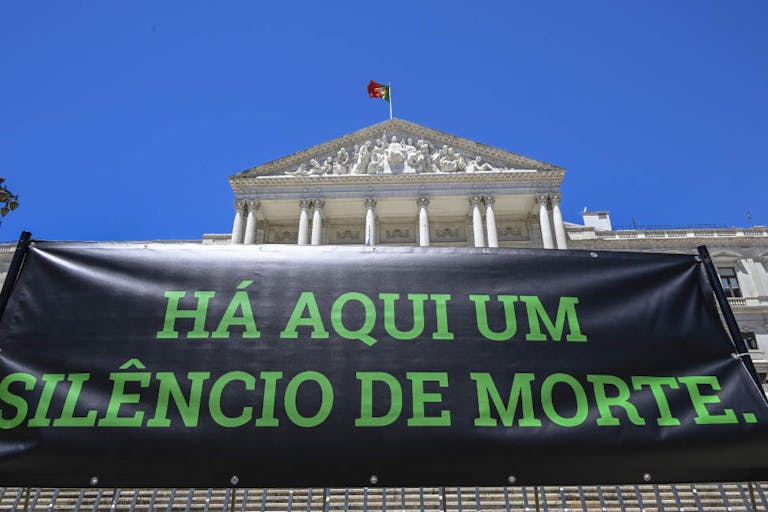

Third attempt to legalize euthanasia in Portugal fails

The third attempt to legalize euthanasia in Portugal has failed. Following Parliament’s latest attempt to legalize euthanasia, Portugal’s Constitutional Court rejected the text of the law. Previously, the court said the language of the legislation was too “imprecise,” and it appears the court still has a similar complaint.

In a statement released to the press, the court said the text had an “intolerable vagueness,” as legislators did not adequately define the “suffering of great intensity” that would be required for physician-assisted death. But Isabel Moreira, one of the parliamentarians behind the bill, said she plans to continue trying to legalize euthanasia.

“If it is a question of correcting a word, we will be there to do so,” she said during a press conference, explaining that the issue was merely one of “semantics.”

Counsellor João Pedro Caupers explained some of the issues the court was having with the text of the bill. “The question at issue is whether or not a patient diagnosed with cancer with the prognosis of a very limited life expectancy, or a patient suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis who is not physically suffering (commonly understood as pain), has access to medically-assisted death that is not punishable,” he said.

André Ventura, head of the Chega political party, said he has requested an audience with President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, to request a referendum on the issue. “This process can only be resolved with a referendum,” he said, saying “an issue of this importance, twice declared unconstitutional by the TC, can only be resolved with the direct participation of Portuguese citizens.”

Previous attempts to legalize euthanasia were struck down by either the court or President de Sousa. The most recent attempt passed Parliament with a vote of 126 to 84, with only seven members of the socialist party voting against it. The current legislation states that the person must be experiencing suffering of “great intensity.” In addition, the term “fatal disease” has been replaced with “serious and incurable disease,” which could allow those who aren’t dying, but have chronic illnesses — like diabetes or cystic fibrosis — to be eligible.

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Nancy Flanders

·

Politics

Nancy Flanders

·

Politics

Rebecca Oas, Ph.D.

·

Abortion Pill

Angeline Tan

·

International

Bridget Sielicki

·

International

Angeline Tan

·

Analysis

Cassy Cooke

·

Activism

Cassy Cooke

·

Pop Culture

Cassy Cooke

·

International

Cassy Cooke

·

Analysis

Cassy Cooke

·