Do most doctors in Malta really support abortion? Here are the facts.

Cassy Cooke

·

Opinion·By Cassy Cooke Nancy Flanders

Two pro-life moms share their stories about prenatal testing: ‘It helps parents prepare’

Recently, The New York Times decided to publicize what pro-lifers have known for years: healthy babies are being aborted due to prenatal screening results that implied they weren’t healthy. The Gospel Coalition responded by questioning if Christian parents should use prenatal genetic testing, and argued that knowing a child has a genetic condition can make parents “less rather than more prepared.” Christian bioethicist Gilbert Meilaender was quoted as saying that parents would fail to bond with their children during pregnancy.

We are two pro-life, Catholic mothers… and we disagree with this claim.

Learning my son had Down syndrome while pregnant

My [Cassy’s] first son was only six months old when I got pregnant again, something very unexpected. My husband, at the time on active duty in the Marine Corps, was due to leave on his second Afghanistan deployment within a few months. We could do the math: he wouldn’t be home for the delivery. But nevertheless, as a military family, we had always known it was a possibility and looked forward to having another baby. At roughly 12 weeks, I underwent the nuchal translucency screening; I had no motivation other than wanting the opportunity to see my baby in an ultrasound a little earlier. His heart was beating, everything looked good to me, and I was happy. But the screening came back with 1 in 6 odds that my son had Down syndrome.

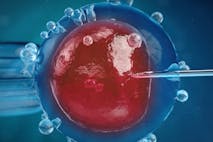

I knew I wanted to know if he did or didn’t. I didn’t want to spend my entire pregnancy worrying about it. So I opted for the amniocentesis, which took place two days after my husband deployed. Three days later, I got the results: male, positive for Trisomy 21, or Down syndrome.

To this day, I am grateful I made the choice I did. Of course, it helps that I had an understanding, pro-life maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist, who never pressured me to have an abortion — but my experience is what every woman in my position should have. I was heartbroken and terrified, but I had the time to grieve and come to accept the diagnosis. By the time Wyatt was born, my husband looking on via Skype, his Down syndrome diagnosis was a non-issue. I didn’t have to cry and mourn while holding my son, thank goodness. I felt guilty enough during my pregnancy for being upset — what kind of mother cries over her own child? — that I can’t even imagine how I would have felt, experiencing those dark emotions while looking at Wyatt’s face.

But the bigger issue with prenatal testing that I wish people knew is how useful it can be, medically speaking. So often, people in the pro-life movement treat it as if it’s only good for deciding to have an abortion, and therefore, if you wouldn’t have an abortion, prenatal testing is pointless. It is true that prenatal testing is used for eugenic purposes far too often, but the culprit isn’t the testing; it’s societal attitudes towards disability. Prenatal testing can be a pro-life tool, far from what people realize.

With Wyatt, the amount of medical attention we received was much higher than what we would have had without it. My MFM was constantly performing fetal echocardiograms, checking his vital organs, measuring his limbs, and many other things to make sure Wyatt was growing and developing the way he should be. He had plans in place in case anything looked alarming, and when it came time for delivery, we were similarly prepared. I was able to visit the NICU ahead of time, so I could be ready if Wyatt ended up there. During the c-section, NICU staff was in the operating room, ready to go, just in case Wyatt gave us any surprises. (He didn’t.) We had a backup plan, a backup plan for our backup plan, and a backup plan for that backup plan. We were READY.

But beyond all of that, prenatal testing is useful for a big reason: it can save your baby’s life.

For babies with chromosomal abnormalities, the placenta is made up of the extra chromosome, too. That means it is more likely to fail, which is likely why so many babies with chromosomal defects (like Down syndrome) are miscarried or stillborn. Because we knew ahead of time, my doctors knew to closely monitor the placenta, with twice-weekly non-stress tests and weekly ultrasounds to measure blood flow. If there had been a hint that the placenta was beginning to fail, Wyatt would have been delivered early so we did not end up with an unexpected stillbirth.

There are undoubtedly problems with how the medical establishment responds to the results of prenatal testing. But the testing, in and of itself, can save lives and be pro-life.

Now, almost 10 years later, I am still grateful for that prenatal diagnosis. I wouldn’t change a thing.

Learning my daughter had cystic fibrosis after birth

My [Nancy’s] pregnancy with my daughter went as smoothly as it could go — barely even any morning sickness. But there was one bit of foreshadowing I overlooked.

Midway through the pregnancy, my sister learned she was a carrier for cystic fibrosis (CF), a genetic condition that causes thick mucus to build up in the body, clogging organs like the pancreas and lungs. In the 1960s, children with CF rarely lived beyond grade school. I told my doctor at my next pregnancy checkup and they realized I had slipped through the cracks. They hadn’t tested me to see if I was a CF carrier.

Article continues below

Dear Reader,

Have you ever wanted to share the miracle of human development with little ones? Live Action is proud to present the "Baby Olivia" board book, which presents the content of Live Action's "Baby Olivia" fetal development video in a fun, new format. It's perfect for helping little minds understand the complex and beautiful process of human development in the womb.

Receive our brand new Baby Olivia board book when you give a one-time gift of $30 or more (or begin a new monthly gift of $15 or more).

Yet, rather than test me as I had expected, they told me not to worry. If I were a carrier for CF there was only a 1 in 400 chance that my husband was too, and he had to be in order for our child to have CF. Even then, there was a 1 in 4 chance that our baby would inherit CF from us. My doctors told me babies were now tested for CF at birth and “It’s not a reason to abort.”

I agreed and I put CF out of my mind.

Minutes after my daughter’s birth, she was taken to the NICU due to a fever. She remained there for four days, but after running tests, doctors couldn’t find anything wrong. We went home. The postpartum emotions took over and I began to experience anxiety about things that could happen 20 years in the future. I was a mess and completely caught off guard when, after two days at home with a baby who pooped and fussed constantly, my husband told me the pediatrician had called.

READ: Prenatal testing, used in a pro-life way, made the difference for these families

That night we learned our daughter had CF. My husband had known someone with CF who died at age 20. I hadn’t even bothered to Google it. When he asked the doctor about life expectancy, he assured us (two 31-year-olds) that people with CF were now living into their 30s. You can imagine our reaction.

It was six o’clock on Friday and we had to wait until Monday to meet the CF team. We were told not to Google CF, so of course I Googled CF and spent the weekend (and the next weeks) crying. I cried over her as she nursed, as she slept. It was as if the words “cystic fibrosis” were tattooed on her forehead.

When we met with the CF team, the nurse, who had been the CF nurse for decades, looked me straight in the eyes and told me that someday we would be dancing at our daughter’s wedding. She knew what I didn’t know and what the pediatrician didn’t know. She had the insight that I would gain over the next few months — the insight I wish I had had months earlier when God had first whispered the words “cystic fibrosis.”

I learned about CF while battling postpartum anxiety and sleepless nights. I met adults with CF who had lived decades beyond the life expectancy they had been given at birth. I still cried all the time and my marriage struggled. It breaks my heart that our daughter spent those first weeks of her life with a sobbing mother. There should have been more joy in those days and in her mother’s eyes.

Thirteen years later, she has never been hospitalized for a CF “tune-up,” and though she has struggled to gain weight and is glucose intolerant, she is healthy. Thanks to Trikafta, a new medication, her lung function is normal, her weight is up, and her glucose will hopefully remain stable. Since her birth, the median life expectancy for CF has advanced more than a decade and is expected to continue climbing. She’s happy, and I wish I had been given the time to learn about CF before she was born so that I could have gone through the tough emotions before being in the throes of postpartum anxiety, which likely elevated the effect of her diagnosis on me.

If my husband and I had been tested to see if we were carriers, we would have known there was a 25% chance she would have CF. I’m not sure I would have done the amniocentesis to confirm the diagnosis due to the risk of miscarriage, but I could have prepared myself. It would have been beneficial in case she had a bowel blockage at birth that required surgery, as 10% of people with CF do. It would have been a blessing to have the enzymes ready so she didn’t have to experience the physical pain of not being able to digest food. It would have been nice for her to have the first weeks of life with parents who understood her needs and were able to meet them.

Prenatal testing means preparation

Prenatal screening and testing is a gift of science that helps parents prepare. Babies with spina bifida can have surgery before birth, increasing their odds of walking. Babies with Trisomy 18 can receive immediate medical care that can save their lives. Parents of babies who will die at birth can have time to prepare and share special moments before birth, rather than being blindsided after birth.

Pro-lifers often say that “it doesn’t matter” if their baby has a health condition, but a baby’s health condition matters and so does a proper diagnosis. Prenatal testing itself isn’t pro-abortion — it’s pro-life. And it does help parents prepare.

“Like” Live Action News on Facebook for more pro-life news and commentary!

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Cassy Cooke

·

Guest Column

Emily Berning

·

Opinion

Nancy Flanders

·

Opinion

Mark Wiltz

·

Opinion

Mark Wiltz

·

Pop Culture

Madison Evans

·