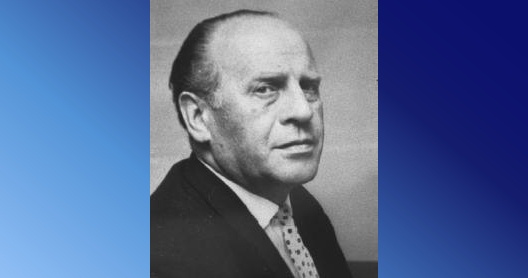

Oskar Schindler

Oskar Schindler: Look, all you have to do is tell me what it’s worth to you. What’s a person worth to you?

Amon Goeth: No, no, no, no. What’s one worth to you?

-Quotation from the film Schindler’s List

Oskar Schindler was born on April 28, 1908 in the town of Zwittau, Morvia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now the Czech Republic. His father Hans Schindler owned a factory, and his mother Louisa was a homemaker. If still alive, Oskar would have recently celebrated his 104th birthday. Schindler was made famous by producer Steven Spielberg’s 1993 Oscar-winning hit Schindler’s List. The movie was a retelling of Thomas Keneally’s 1982 novel Schindler’s Ark. Both book and film were inspired by Holocaust survivor and Schindler’s former factory worker Poldek Pfefferberg.

Schindler was a pleasure-seeking German businessman and member of the Nazi party. He married Emilie Pelzl, the Catholic daughter of a wealthy farmer. In 1939, when Poland was occupied by the Nazis, he purchased an enamelware factory in Krakow. He benefited by hiring workers from a nearby ghetto to supply him with cheap labor. As Nazi persecution grew, Jews were being shipped off to labor camps and killed in the streets. Shindler, disgusted by the sheer cruelty of the Nazis, decided that he would do what he could to save lives.

Later, when news broke that only those factories essential to the war would remain open, Shindler convinced German officers to let him relocate his factory and use it to make ammunition. This is where his well-known list came in. It comprised a thousand people who would travel to the new factory. He made sure his workers never produced one working shell to be used in the war. The factory was solely a place of refuge for the Jews.

As the war progressed, Schindler and his wife gave their personal fortune to protect their Jewish workers from death. Keneally’s book reports: “Oskar was paying nearly $14,000 US each week for male labor; when the women arrived the bill would top $18,000. Oskar was therefore committing a grand business folly.”

From distracting SS officials with liquor to getting supplies from the black market, Schindler used whatever means necessary to provide food, shelter, and safety for the Jews he loved. When Jewish families were being separated all throughout Europe, Shindler fought for them to stay together. He changed records so elderly men, deemed useless by the Nazis, became twenty years younger, and children were recorded as adults. He spoke on behalf of handicapped people by convincing the Gestapo that they were necessary to him as mechanics and metalworkers. Schindler was brought before Nazi officials for accusations of gambling and favoring the Jews. Though he was jailed multiple times, his charisma and connections always got him released.

Even though they were risking their lives, the Schindlers never saw themselves as heroes. They merely felt that they were doing what they had to. Oskar later said concerning his actions, “If you saw a dog going to be crushed under a car, wouldn’t you help him?” It was as simple as that.

Schindler was not a perfect role model. He had numerous affairs and was a known womanizer who eventually abandoned his wife. He was called a drunkard and a gambler who spent many years foolishly wasting money. Failed business attempts after the war led to him being penniless at death. He depended on the generosity of the Jewish organizations and the survivors from his factory in the latter years of his life. He was hated by many in Germany and found acceptance and love among his Jewish friends and during his yearly visits to Israel.

For all his mistakes, Oskar was a remarkably courageous man who risked his life to save 1,200 people. He had no biological children, but he referred to the the survivors of his factory and their descendants as his own. His story proves that flawed men in the face of evil can still do what is right.

Oskar wasn’t religious; he wasn’t motivated by his faith or even by his political views. His conscience testified that the murder and mistreatment of human beings is evil. When Shindler saw innocent people being put on trains bound for death, he said, “Beyond this day, no thinking person could fail to see what would happen. I was now resolved to do everything in my power to defeat the system.”

What will the history books say of us? Are we like Oskar, willing to spend our money, time, and energy to save human lives? Would we risk imprisonment and even death for the sake of another? Could we stand against popular opinion, corrupt government, and social pressures to be a righteous voice in a wicked nation? Six million Jews were killed in the holocaust. Over 54 million babies have died from our holocaust of legalized abortion. What is our response to this mass murder?

We can distance ourselves from the truth and argue that a fetus isn’t as valuable as an adult. Our justifications may bring false comfort, but at what cost and for how long? We’ve seen the graphic photographs of human bodies piled together in dirt pits and of naked corpse-like figures standing in gas chambers. We know of the Nazis’ experiments and the inhumane acts done for “research.” While time has passed, and their evil has been exposed, ours is left conveniently hidden.

What if we could see past the shiny pink Planned Parenthood signs? What if we got a good look at what really happens in clinics and hospitals across our nation? What does that bloodshed look like? Babies dismembered and left in buckets to die. Children’s bodies burned by chemicals and gathered by the thousands to be cremated. Scientists using aborted baby parts for medical experiments and cells for beauty creams. Sound familiar?

We can condemn the German people for their silence, but what will we say about ours? It’s not easy to stand for life, but it’s always the right thing to do. Shindler proved that saving a life is worth giving up your fortune, risking your safety, and losing your reputation. He may have died penniless, but he was a rich man in ways money can never buy. His life is an example to us all.

Schindler’s body is buried in a Catholic cemetery in Jerusalem. The Hebrew inscription on his tomb reads, “A righteous man among the Gentiles[,]” while the German one says, “The unforgettable lifesaver of 1,200 persecuted Jews.”