Is picking the 'best' embryo a mere parenting tool, or eugenics fueled by hubris?

Nancy Flanders

·

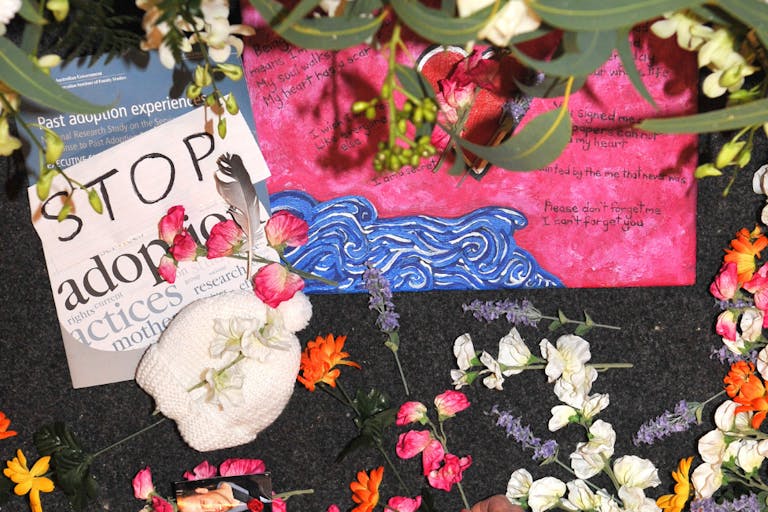

‘Irreparable damage’: Australia reckons with tragic history of forced adoption

The effects of a decades-old policy of forced adoption in Australia continue to haunt many of the estimated tens of thousands of women who had their babies forcibly taken away by the government, and who remain traumatized despite government efforts to make amends.

Tricia Lester gave birth to her only child in 1972 in Melbourne, when she was 18 years old. Under the Australian government’s forced adoption policy – which was official from 1958 to 1984 but extended earlier and later than those years – deemed her too young to be a mother and unable to properly care for her newborn, and decided she was “unfit” because she was unmarried. Now in her 70s, Tricia reunited with her son 20 years ago, but his initial loss continues to be a source of pain decades after.

“You get by because you live your everyday life but I still struggle with my sense of worth, my sense of identity and an enormous sense of loss,” Lester said, according to the Port Stephens Examiner. “I would have thought 50 years later I would stop weeping but there’s still days I weep.”

Another woman, Merle Kelly, gave birth as an unmarried 17 year old in Victoria in 1961. During delivery she was put under anesthesia, and when she awoke her baby had already been taken away. Kelly was not allowed to see her baby until they were reunited decades later, and despite trying to move on with her life, the damage was profound.

READ: Elder abuse is flourishing in Australia as assisted suicide grows

“I just had a totally new life and I just had to bury it — I think that’s why it’s hitting me so bad now, 60 years later,” Kelly told ABC News in Australia. “It has just caused total, irreparable damage.”

In 2013, the Australian government officially apologized for the policy of forced adoption, and in response to a parliamentary inquiry in 2021, reports the Port Stephens Examiner, Australian Premier Daniel Andrews announced a $4 million redress package to provide compensation and support for mothers affected, because even though the policy of forced adoption has ended, women continue to have lasting effects from the policies around pregnancy and childbirth.

But as tacitly acknowledged in certain articles discussing the practice, the forced separation didn’t end with forced adoption; it was replaced by the availability of abortion.

Abortion is another form of forced separation, even if it is a mother’s “choice.” Then as now, rather than providing critical support for women experiencing unplanned pregnancies, governments and influential voices in society often promote abortion as the “solution” for women, exerting behind closed doors much of the same kind of pressure on many women openly experienced in days past.

Despite the progress on forced, closed adoptions, all states and territories in Australia have legalized abortion, including many that allow abortion until birth, as Australian pro-life advocacy group Life Choice has documented. Additionally, pro-life doctors are forced to provide information on abortion to patients, and all abortion facilities are protected by 150 meter exclusion zones that make it illegal to even pray near them. The government also subsidizes abortion through its state healthcare plans.

According to Wattle Place, the trauma of families separated by forced adoption reverberates throughout the generations, and many women experience lasting trauma, PTSD, isolation, and shame, especially around triggering events like birthdays. Men also experience the trauma of families being torn apart. Similarly, as all too many women know, the sudden interruption and disposal of a preborn child in abortion can have similar effects on women and men, as well.

Multiple studies have shown that most women – as many as 81% according to one British journal – are at an increased risk of lasting psychiatric problems including depression, as Live Action News has reported. As Right to Life Australia’s website noted, “Some women report feeling an immediate feeling of relief following an abortion, but many find themselves later coping with feelings they did not expect and were never warned about. They may have a hard time talking about, acknowledging or even relating these feelings to the abortion.”

The legacy of forced, closed adoptions is one of broken lives and broken families. Time will show that the legacy of abortion, whether wanted or unwanted, will be the same.

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Nancy Flanders

·

International

Nancy Flanders

·

International

Cassy Cooke

·

International

Bridget Sielicki

·

International

Cassy Cooke

·

International

Bridget Sielicki

·

Human Interest

Laura Nicole

·

Human Interest

Laura Nicole

·

Newsbreak

Laura Nicole

·

Human Interest

Laura Nicole

·

Human Interest

Laura Nicole

·